In the end, we’d like it all to add up. The simplest way for things to add up is through counting. If we’ve got a pile of candy, or money, counting to a higher number is considered a better result. In golf, fewer strokes makes a lower score and thus determines the winner. Another way we add things up is to make a whole. Two arms, two legs, a nose, a mouth, et cetera and at some point we have a body. This kind of mathematics is the basis of the crime drama.

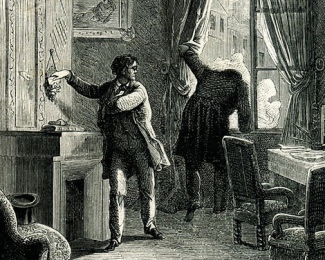

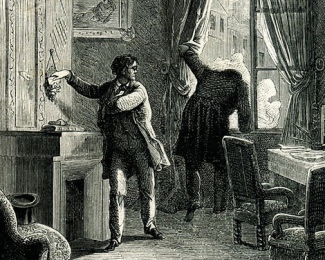

Sherlock Holmes adds things up to create an image of a crime and a criminal. A dog that didn’t bark, a bit of cigarette ash, a kind of writing paper and ink and a print of an uneven heel in the mud flash into a kind of picture of the prime suspect. One of the pleasures of the Holmes stories is following along a chain of deductive reasoning that only seems reasonable in hindsight. Television channels are stuffed with one-hour dramas using Conan Doyle’s template. As we read, or more likely watch, there’s the feeling of a conjuring trick— the creation something out of nothing. Even though, as Holmes likes to say: “You know my methods…” Implied is a sort of mathematical reasoning that operates like a logical sorting machine. Anyone making proper use of the machine would come to the same result, like counting apples in a basket.

The other night I was reading a story featuring a precursor to Holmes. Here the amateur detective is C. Auguste Dupin. The story, written in 1844 by Edgar Allen Poe, is called “The Purloined Letter“. The Prefect of Police has come to Dupin to discuss the case of a letter stolen by a Minister and hidden somewhere in his house.

Dupin’s exploration of the case with the story’s narrator, his version of Watson, begins with an assessment of mathematics, poets and fools:

This functionary, however, has been thoroughly mystified; and the remote source of his defeat lies in the supposition that the Minister is a fool, because he has acquired renown as a poet. All fools are poets; this the Prefect feels; and he is merely guilty of a non distributio medii in thence inferring that all poets are fools.”

“But is this really the poet?” I asked. “There are two brothers, I know; and both have attained reputation in letters. The Minister I believe has written learnedly on the Differential Calculus. He is a mathematician, and no poet.”

“You are mistaken; I know him well; he is both. As poet and mathematician, he would reason well; as mere mathematician, he could not have reasoned at all, and thus would have been at the mercy of the Prefect.”

“You surprise me,” I said, “by these opinions, which have been contradicted by the voice of the world. You do not mean to set at naught the well-digested idea of centuries. The mathematical reason has long been regarded as the reason par excellence.”

Then as now, the “mathematical reason” is regarded as reason par excellence. The Prefect of Police has brought in microscopes and measuring sticks to search every speck of the Minister’s house. He’s been very methodical, no stone has been left unturned. We would expect Dupin to defend mathematical reason as the ne plus ultra, the method that trumps all other methods. The mechanical method that produces a correct result regardless whether humans believe it or not. Instead he launches in to a discourse on the limits of mathematical reason:

“I dispute the availability, and thus the value, of that reason which is cultivated in any especial form other than the abstractly logical. I dispute, in particular, the reason educed by mathematical study. The mathematics are the science of form and quantity; mathematical reasoning is merely logic applied to observation upon form and quantity. The great error lies in supposing that even the truths of what is called pure algebra, are abstract or general truths. And this error is so egregious that I am confounded at the universality with which it has been received. Mathematical axioms are not axioms of general truth. What is true of relation –of form and quantity –is often grossly false in regard to morals, for example. In this latter science it is very usually untrue that the aggregated parts are equal to the whole. In chemistry also the axiom falls. In the consideration of motive it falls; for two motives, each of a given value, have not, necessarily, a value when united, equal to the sum of their values apart. There are numerous other mathematical truths which are only truths within the limits of relation. But the mathematician argues, from his finite truths, through habit, as if they were of an absolutely general applicability –as the world indeed imagines them to be. Bryant, in his very learned ‘Mythology,’ mentions an analogous source of error, when he says that ‘although the Pagan fables are not believed, yet we forget ourselves continually, and make inferences from them as existing realities.’ With the algebraists, however, who are Pagans themselves, the ‘Pagan fables’ are believed, and the inferences are made, not so much through lapse of memory, as through an unaccountable addling of the brains. In short, I never yet encountered the mere mathematician who could be trusted out of equal roots, or one who did not clandestinely hold it as a point of his faith that x squared + px was absolutely and unconditionally equal to q. Say to one of these gentlemen, by way of experiment, if you please, that you believe occasions may occur where x squared + px is not altogether equal to q, and, having made him understand what you mean, get out of his reach as speedily as convenient, for, beyond doubt, he will endeavor to knock you down.”

In the era of “Big Data” the computational power at our disposal is enormous. Big Blue can play chess or the game show Jeopardy. Google Now has a pretty good chance of predicting what you’ll do next and the data set that might prove useful in doing it. Even the NSA and the CIA, continuing the efforts started with ‘Total Information Awareness’, have started collecting and saving every electronic digital trace that is collectable. “Big Data” gives us the sense that we’re seeing high resolution, at zillions of pixels per inch. We could even say that we’re seeing at a resolution that far outstrips the organic capacity of the human eye. It’s in the mind’s eye that this new kind of picture comes into focus.

Just as with the Prefect of Police, there’s an illusion of high-resolution clarity that comes with Big Data. We think we’re seeing everything there is to be seen. And further, that with sufficient amounts of data, all answers will clearly present themselves. I wonder what will happen when we have all the data there is to have and we still can’t find the purloined letter.