It’s with the digital that we imagine we’ve made the bits small enough to get to the bottom of things. Nothing is smaller, more atomic, more essential, than those ones and zeros that make up the digital. With high-definition 3-D digital motion pictures we appear to capture things perfectly, to get to their essence, their reality. In some cases, the digital simply replaces a thing. What was encoded on vinyl records is now bits in a file on a hard disk or flash memory. An image once printed to photographic paper is now just flashed on a screen as part of an ongoing slide show.

This notion of capturing the essence of something surfaced recently while reading an essay by Ulrich Pfarr on the painter Gustave Courbet in the book “Courbet: A Dream of Modern Art.” The essay looks at how the quality of “introspection” is conveyed in the portraits painted by Courbet. Of course, a portrait is also meant to capture something of the essence of a person. It’s not a snapshot, or a documentary representation of how a person looked at one particular tick of the clock. We understand that the portrait captures a general way of being of a person. Here’s Pfarr on Courbet and portraits:

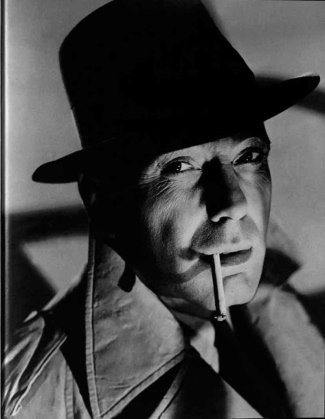

Conspicuous eyebrow movements are also a feature of the Rembrantesque chiaroscuro in the portrait of art dealer H. J. Van Wisselingh. As a consequence of the hard incidental light, the drawn, furrowed eyebrows cast the eyes into shadow, so the nerves are not tense and therefore the eyes are not narrowed. In this way, the expressive touch of anger in the eye area is toned down into a sign of inner concentration that, combined with the slight tilt of the head, is condensed into the image of an energetic personality. Of course, this may reflect not Van Wisselingh’s inner constitution so much as his professional mask. To that extent, Courbet, who complained that Baudelaire looked different every day, seems to have only a limited interest in the dubious ability of the physiognomy to offer indications of psychological traits in fixed physical features. Although these pictures confirm Courbet’s endeavors to filter permanent features from transitory visual phenomena, the deeply etched traces of facial movements are in turn adjusted in favor of the subjective impression you only get from a living sitter, which art theory traditionally calls an “air.”

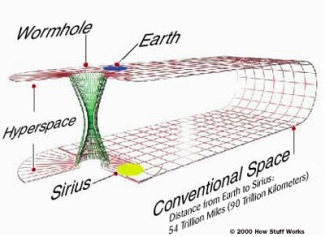

Following phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty, we might imagine that the essence of a thing could be definitively determined by statistically analyzing every possible profile a thing presents to us. We might easily conclude that the essence of a thing is, what it mostly is. There’s a kind of democratic quality to this approach; as though inside each thing an election could be held with its essence determined by a majority vote. Normativity rules. In this kind of big data scenario, the concept of “essence” is hedged through the use of words like “propensity” and “probability.” Our actions with regard to a thing tend to line up with the majority — we act as though we perceive an essence. We’d be fools to buck the odds.

Going back to Courbet’s portraits, there’s a kind of compression of observation that produces an essence. The resulting essential painted image may very well be outside the actual collection of observed data. Here the expression of essence might be different than any one thing perceived or recorded about a thing. But a thing’s essence is more than just an average or composite of the majority, it’s the unique minor elements that create all the specificity. In fact, the expression of essence in a portrait is fully contained in the small differences.

When we look at a thing, we see it at a certain tempo. You can think of this as “beats per minute.” A tune can be played within a whole range of beats per minute. Returning to a charged memory at a later time, we can play it back at a slower speed. We become the director and editor of our memory, shaping it to fit its purpose. William Wordsworth wrote about this process in his preface to the “Lyrical Ballads.”

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. In this mood successful composition generally begins, and in a mood similar to this it is carried on; but the emotion, of whatever kind, and in whatever degree, from various causes, is qualified by various pleasures, so that in describing any passions whatsoever, which are voluntarily described, the mind will, upon the whole, be in a state of enjoyment.

We can see new aspects of a thing by changing the tempo. Jean Luc Godard’s 1980 film “Slow Motion” (also called “Sauve Qui Peut” or “Every Man for Himself”) gives us some memorable examples of this phenomena. There’s a scene that has stuck with me since I first saw the film; it’s sequence where Nathalie Baye rides a bicycle through a country landscape. Occasionally the film slows down and stops on a frame for a moment. Out of this fluid bike ride, these very poignant sculptural moments are carved out. Suddenly we see the outward signs of the inner world, the quality of introspection becomes visible. A simple bike ride is revealed to contain an infinity of interior space. Nothing about the real-time video recording contains those moments.

If we were to look at the world through the eyes of the objects around us, we’d see at varying tempos. The rock has a slower tempo than the honey bee, the electron has a faster tempo than a pumpkin. As humans, we tend to think of the music of the spheres all moving at the same tempo. A single beat holding down the discotheque of the universe — a human beat. Viewing a stop motion film of a flower growing and blooming, we can clearly see that plants dance to a different beat. Sunlight, soil and the plant all relate at the plant’s tempo. Humans require the technology of stop-motion photography to speed plant tempo up to human tempo so that it becomes visible to us.

Returning to our starting point, we ask whether the digital as a medium has any particular advantages in capturing the essence of a thing? Certainly it has reduced the cost of certain kinds of reproduction. Video, still image and sound recording have been made much simpler. With our big data systems we’re able to create very large haystacks where previously invisible patterns suddenly emerge. Is there a simple method that combines raw digital capture and algorithmic computation on big data sets that results in a picture of the essence of a thing? Or as it would be said in the lingo, a “high probability” of the essence of a thing? Could it understand the introspection of a thing operating at a radically different tempo? Do androids dream of electric sheep?

Imagine if this kind of encoding were done using oil paint. Again, here’s Pfarr on Courbet:

Comments closedCourbet has a whole repertory of techniques to suggest the gradations between half-sleep, falling asleep, waking up, and daydreaming, ranging from wide-open eyes to the features of deep sleep. Figures with eyes half or completely closed feature sitting upright, smoking a pipe, or holding a cup, like “The Lady on a Terrace” — in all these cases, the facial expression does not function as an empirical physical symptom but indicates various gradations of mental introspection.