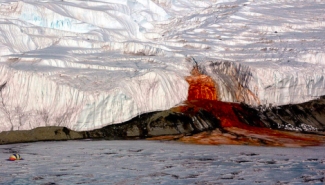

A simile is a kind of metaphor. Rather than saying this noun “is” that noun, we say it is “like” that noun. We insert a little distance between the two things. The bleeding glacier in Antarctica is like a wound in the ice.

Our first instinct in viewing the photograph is to ask what it “really” is. That’s not really blood, what is it? I mean scientifically.

Taylor Glacier in Antarctica’s McMurdo Dry Valley, in 1911, is in fact the run-off from a microbe-filled lake deep beneath the surface of the glacier. The run-off seeps out through a fissure in the glacier, and it is red not because the poor microbes are bleeding, but because it comes from a very iron-rich environment.

The power of the image is defused in its scientific explanation. It’s iron-rich microbe run-off. That’s not blood. The ice isn’t wounded; it isn’t bleeding.

Blood is a bodily fluid in animals that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

The image is arresting, it’s like the ice is bleeding. Even in this remote place at the bottom of the world, the earth has suffered a wound and bleeds into the ocean. What does it mean that the earth shows the signs of a stigmata? Why does the earth bleed from this glacier of ice? Does the earth grimace in pain?

How would we view this image differently if it was created by the artist Andy Goldsworthy? Is it only through the medium of an artist’s work that it can be considered and read as a work of art? Today we say that an artist is a genius. “Genius or Genii” was once what we called the attendant spirit of a place. Imagine that this mass of ice, flow of microbes and change in temperature joined forces to create a work of art — an image that is meant to resonate and find a permanent home in your mind’s eye.