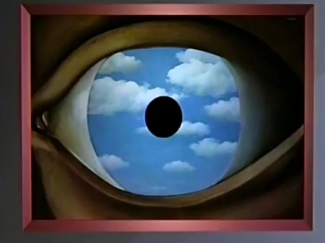

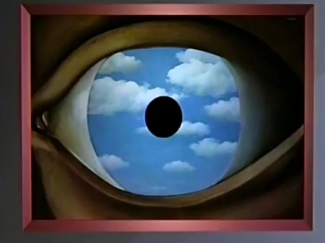

There was a moment in time when the internal cinema of the mind opened its doors for business and began selling tickets. It might have been in 1798 when “Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems” by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge was published. This cinema of the mind was invoked through the use of unrhymed iambic pentameter, or blank verse. Squiggles of black ink sequenced in a particular rhythm were put down across rows on a sheet of paper. They were designed to induce hallucinations, to operate like a time machine that brought you back to a moment of powerful feeling — pried open your eyes and allowed you to witness that scene as it actually comes to exist in your mind.

From the Preface to the “Lyrical Ballads” by William Wordsworth:

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.

“Spots of time” was the phrase Wordsworth used to describe these powerful feelings that welled up spontaneously, overflowing any effort of reason to contain or define them. Contemplated from a tranquil distance, these are the springs the feed the continuing power of poetry. Defying entropy, these moments don’t strike and fade to nothingness. As Freud would later note, they become constitutive of our identity — in both our joy and our madness. They are the personal identity that persists through time and one source of poetry.

From William Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” (1805 edition):

There are in our existence spots of time,

That with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence–depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight,

In trivial occupations, and the round

Of ordinary intercourse–our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired;

A virtue, by which pleasure is enhanced,

That penetrates, enables us to mount,

When high, more high, and lifts us up when fallen.

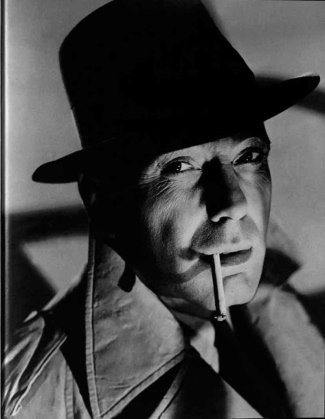

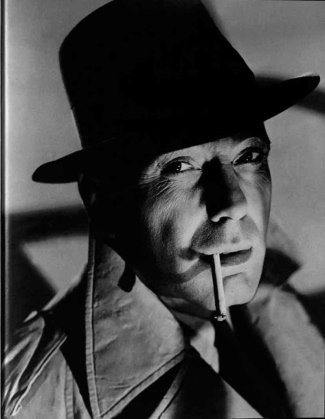

One of the pleasures of the murder mystery genre is this quality of inducing an internal vision of a past moment of intense passion. The detective surveys the scene of the murder and attempts to reconstruct the events. Witnesses are interviewed, asked to tell what happened. As the witness recounts her memory of the event her eyes shift their focus inward. The internal cinema fills her mind’s eye; she sees those moments around the crime as though they are occurring right now. She puts the vision on a loop and attempts to put it into words. In her face we can see the emotions evoked by remembrance and a reflection of the power of emotions from the event itself. The witness’s words evoke a vision in the mind’s eye — for both us and the detective. As each witness tells some piece of the story, we replay the vision, adding details, attempting to piece together a coherent narrative to replace the mystery.

In film versions of murder mysteries, the eyes of the detective are the key to understanding the kind of thing that will have to be imagined to solve the crime. The world-weary detective in a film noir has seen it all. The character of his eyes gives us a sense of what he could imagine. As he loads the witness’s stories into the projector of his mind’s eye, he must let them induce whatever visions may come. Often we can see how this process of envisioning has taken its toll on the face and eyes of the detective. In others, say the Miss Marple mysteries, we see an incongruous contrast between the seemingly normal countenance of the detective and the eyes that can imagine horrific events of violence. The internal capacity of a dark and powerful imagination doesn’t always correspond with the external physique of an action hero.

There’s a moment when everything clicks. Often it’s a moment that seems to be a break in the story. The detective, exhausted from gazing at the movie he’s constructed, turns off the projector and re-enters the world. An off-hand remark, a simple gesture, a common object seen in a new light offers the analogy that the provides the key. The puzzle pieces of the internal vision sliding around the detective’s head suddenly form a pattern with the ring of truth. This marks the beginning of the end of the story. Often at this point all the suspects and witnesses are gathered together in a room for a recitation of the detective’s vision. “Now you’re probably all wondering why I brought you here today.” Validation takes the form of the murderer making a break for the door.

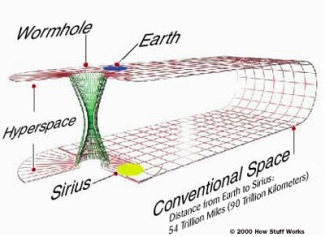

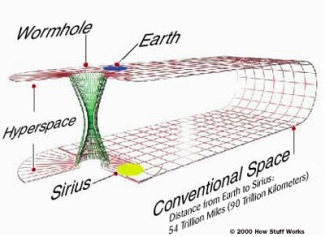

In the future in which we currently reside, this method of scraping a valid account out of the internal memories of unreliable witnesses begins to seem horribly inefficient. Imagine, if you will, how it might go. The detective arrives on the scene of the murder. The victim is positively identified and the paperwork is filed.

The panel reviews the particulars of the crime and determines whether or not the victim’s black box should be released to the detective and which time machine privileges should be granted. The black box is the victim’s personal network cloud, along with all it’s corporate, medical and government cloud counterparts. This includes a stream of all commercial and financial transactions, social media transactions, voice and text mobile communications, location and personal quantification data. A unique identifier is generated to tie all the person’s data streams together into a single life stream. When loaded into the black box player, the detective can replay the victim’s life from any arbitrary point in time prior to the murder up until the time of death and after. Some data streams don’t require a living subject. The victim’s social graph and location data is used to aggregate all still and video photography relevant to the time in question. A list of additional persons of interest is generated through a strong tie / weak tie analysis of the people the victim came into contact with.

The persons-of-interest list is submitted to the panel for approval. Once approved, this gives the detective the ability to more fully explore what happened along multiple vectors. When the additional black boxes are loaded into the time machine, the detective can travel through multiple vectors and get a real 360 view of the event. The additional data really increases the resolution of the time travel experience. For murder investigations the data also includes all digital communications with built-in auto-erase functions and any sort of strong encryption.

With the data set constructed, the detective initiates the search algorithm. Based on analysis of motive, opportunity and other risk factors the top three suspects with the highest probability are identified. The paperwork is filed to allow the detective to show the prime suspects the highest probability version playback of what occurred. Each suspect is hooked up to biometric measuring machines and shown the playback. Through an automated analysis of the biofeedback the most probable murderer is identified and charged with the crime. The detective then converts the data set to an evidence set for the district attorney. The evidence set includes provenances and audit trails for all the data included.

Physicists disagree about whether time travel is possible. Given the speed of light and the size of the universe, it’s certainly possible to view ancient events as though they are happening in the current moment. Just go out on a clear night and look at the stars. But seeing old light isn’t the same as traveling to the time in which the image in that light was created. Whether or not time travel is possible in the physical universe, it’s now possible through the large repositories of time stamped stream data that we’re collecting — these so-called haystacks.

On the other hand, these are just words on a page. They’re designed to cause you to imagine a particular future, to view a movie on your internal cinema screen. They may just be a thought experiment — mere ephemera of the moment. You know, the stuff that dreams are made of.