It might be a way for a television show entering its final season to tell the audience that the empire built up by the main character over the years is about to come apart. That’s where Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet “Ozymandias” makes an appearance.

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—”Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

A poem may have a use as a preview for a television series. It might provide a comment on the inevitable decline of empires built through raw power. On our sofas in front of our big screens, at our desks gazing at computer screens, on our smart phones as we navigate the foot traffic of the sidewalk, we hear the poem and put it into the context of the story arc of a television show. From the safety of our media consumption dens we see the folly of powerful empires in the face of the sands of time. The show, by means of the poem, tells the audience about a particular way to watch the show. More than half a million people heard Shelley’s poem in the five-day period after it was published to the Network. In this context, the poem has a certain utility, but it also bursts out of that frame.

Shelley thought of a poem as a message in a bottle from the future. A powerful poem, this one was written in 1818, continues to deliver messages to the present for a good long time. The poem remains in the future until it has no more it can tell us. “Ozymandias” continues to speak.

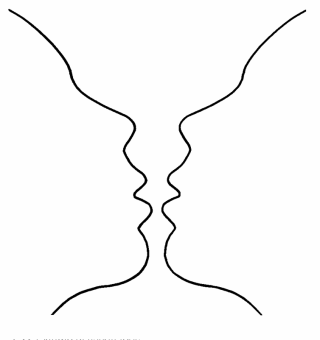

The poem’s construction gives us a whole series of nested narrators, interlocking boxes of perspective. We, the readers, are also implicated in this chain of perspectives. It turns out that “we” are Ozymandias, it might be us speaking those words that appear on the pedestal. As we appear to have a relation to the broken and buried stone figures of Ozymandias, so will future civilizations have that same relationship to us.

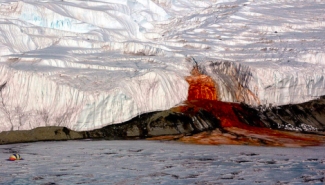

The desert of Shelley’s poem brings to mind the landscapes of Craig Childs’s “Apocalyptic Planet“. Childs visits landscapes of heat and sand, ice and wind, and fields of volcanic lava. He returns to us a traveler from an antique land. He winds up his Long Now Foundation talk on his journeys with the place he called the most terrifying apocalyptic landscape. Childs and a friend hiked and camped for two days and three nights in an Iowa GMO corn field. For Childs the corn field has much in common with the other apocalyptic landscapes he visited. These are places where the earth becomes “lots of one thing and not much of any other.” King corn has a message written into its DNA. The pesticides carved into the pedestal of its genetic code are a broadcast message to any living entities who might enter its empire: “look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

The other message delivered in this reading of Shelley’s poem has to do with what attitude, what feeling, we get from the ruins of Ozymandias’s broken stone statues. There’s the “frown and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command” and the command to “look on my Works and despair.” We get the feeling of a civilization built on the fear of power — of the many living in fear of the few. If we are Ozymandias, what message we will leave behind for a future generation to ponder?

It’s here that the writer George Saunders’s commencement speech to the students of Syracuse University emerges in the poem. As an older person he wanted to tell this group of young people, with their whole lives ahead of them, what he regretted in his life. And here’s the message written on his pedestal: “What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness”. George Saunders is also Ozymandias, but an Ozymandias who has read and been affected by Shelley’s poem.

So, quick, end-of-speech advice: Since, according to me, your life is going to be a gradual process of becoming kinder and more loving: Hurry up. Speed it along. Start right now. There’s a confusion in each of us, a sickness, really: selfishness. But there’s also a cure. So be a good and proactive and even somewhat desperate patient on your own behalf – seek out the most efficacious anti-selfishness medicines, energetically, for the rest of your life.

Do all the other things, the ambitious things – travel, get rich, get famous, innovate, lead, fall in love, make and lose fortunes, swim naked in wild jungle rivers (after first having it tested for monkey poop) – but as you do, to the extent that you can, err in the direction of kindness. Do those things that incline you toward the big questions, and avoid the things that would reduce you and make you trivial. That luminous part of you that exists beyond personality – your soul, if you will – is as bright and shining as any that has ever been. Bright as Shakespeare’s, bright as Gandhi’s, bright as Mother Theresa’s. Clear away everything that keeps you separate from this secret luminous place. Believe it exists, come to know it better, nurture it, share its fruits tirelessly.

Saunders’s consciousness has been upgraded by the poetry of English romanticism. It’s not just that the sands of time have buried and broken this antique emperor named Ozymandias, but that only a small piece of that culture survives. For Saunders, we read this command from the pedestal: “err in the direction of kindness.” The poem asks you as you read it: “What is your message in a bottle for the future?”