Something must be missing. That’s the only possible explanation. Otherwise we humans would naturally live for ever and approach a much higher level of consciousness. It’s as plain as the nose on your face. And while each of us is different, the thing each of us is missing is always imagined as a single common ingredient. It’s a special commodity that once discovered can be sold or given to the entire human race in a transformational act that will fundamentally change the course of human history.

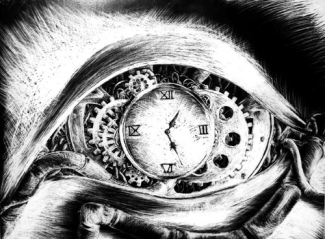

It might be water from a particular fountain or some kind of plant seed from deep in the darkest jungle. The first step is eternal life. Then with time and mortality taken out of the picture we can get down to the business of some kind of perfection. That moment will mark the beginning of the end of our quest.

In the age of networked cloud-based technical solutions, we see this missing piece as coming from computation. Wireless mobile computing puts vast amounts of information at our command or at least within reach. But this is an augmentation, not a filling in of a lack. In the religion of the singularity, it’s the body itself that functions as the flaw. Once the immaterial intelligence (our infinite internal space) is uploaded into an eternally existing industrial cloud computing complex, the fun gets started. The parts that wear out can now be replaced, and replaced with newer and better parts ad infinitum.

Between now and eternal life, there will no doubt be some interim steps. For instance before the body can be confidently discarded and replaced with electronic machinery, it’s likely that we’ll keep our bodies and use ever more sophisticated robots on the side. Even now the replacement of all types of workers with robotic processes is accelerating. We can easily imagine all types of work will soon be replaced with advanced robotics plus big data computation.

Imagine. At birth we’ll be given our first robot. The robot will be assigned to do whatever labor we might have had to do in the past. Credits will be deposited in our account as compensation for the robot’s labor. Everyone will receive a base model robot. Those with more means will be able to augment their robots to do more advanced and highly compensated tasks. And of course, this being the land of the free and the home of the brave, any robot has the potential to be augmented in such a way that it could do the job of President of the United States for somebody. In the eyes of God and law, all robots are created equal. The key political moment was when it was decided that every single person was to be given a robot as a basic right. Initially there was an objection based on the cost. But once robots were building robots from materials obtained and processed by robots, the cost of robots began to approach zero. There were plenty of robots to go around.

And then a day arrives, and we leave our robots behind. Our bodies stop functioning optimally and we agree that it’s time to upload ourselves into that big computer in the sky. At first people held out as long as possible, waiting until they were quite elderly before uploading. More recently, as soon as the bloom of youth is off, an upload may be considered. Our robots can then be reconditioned and assigned to the new people being born into the world. Recycling is so important.

Some people will resist this final exit from the material plane. They’ll spread nasty rumors that the reason robots have been able to replace every possible human job is that they’re actually powered by uploaded souls. The uploaded souls that we think were talking to are really just simulations based on a person’s historical tendencies as encoded in a big database. An actual soul is required to make a robot fully operational for any human capacity, whereas people living in the material world are easily fooled by a simulation of a human. Once the Turing Test was routinely cracked, it wasn’t hard to create satisfactory simulations for each of us. Even the simulations can’t tell simulations from the real thing.

The fantasy of immortality has found various forms over the years. The singularity is just the most recent concoction. But the replacement of labor by robots / machines is a definite reality. One can think of each of the major appliances in an American home as the equivalent of a servant. Labor continues to be displaced by machines, which is a good thing until a majority of people can’t afford to buy a machine of their own.