The song called ‘Big Brother’ by David Bowie keeps playing in the background of my thoughts. Of course, it’s all the noise about NSA and the Big Data work they’ve been doing to try and anticipate terrorist threats. It’s what we asked them to do, and now we’re shocked that they’ve gone and done it.

Someone to claim us, someone to follow

Someone to shame us, some brave Apollo

Someone to fool us, someone like you

We want you big data. Big data.

There’s a book by Shane Harris called “The Watchers” that provides a pretty good history of the effort. John Poindexter is the godfather of Prism and the efforts to use big data techniques to combat terrorism. Although Poindexter’s plan to build audit trails and anonymity into the original system were left by the wayside, the system we have is the one he imagined.

We want zero terrorists attacks, which means we have to stop them before they occur. Like a novel by Philip K. Dick, we have to anticipate the bad guys and stop them before they can act. It’s an impossible demand. Some will say this should be left to law enforcement— good old fashioned police work. And that’s fine if you want to catch the bad guys after the fact. Law enforcement isn’t going to stop a terrorist before the bomb explodes. And if you want to stand up and ask “why couldn’t our intelligence agencies have prevented this?”, then you have to acknowledge that Big Data, and your data, is baked into the cake.

The news media has done shameful job of reporting the story, and they don’t seem to care. The news seems to be about the court-ordered collection of telephony metadata and the potential for collection of specific datasets from the major cloud platforms as a result of court orders. The bloggers working for newspapers prefer to type up their nightmares instead of reporting the story. And, of course, printing nightmares is a good way to create pageviews. The more fear they can create the better. To anyone paying attention, this story has been well known for years.

The house seems to be filled with big brothers, we find them at every turn. Every corporation, organization and government aspires to be a big brother. When big brothers protect us, or give us “free” cloud-based applications, we applaud them. When we begin realize the guns used to defend us could be turned and used against us, we panic. Almost anything can be used as a weapon these days. Take a close look at Jeff Jonas’s real-time sensemaking systems that use context accumulation. Yes, like John Poindexter, he’s baked privacy in from the start. But if that system was pointed at you, there’s very little it couldn’t find out. You can buy that system from IBM.

The nightmare government with total access and control seems to have its roots in the figures of Alp and Mare — the elves that ride you in your sleep without your knowledge or permission. It’s as though the government is dead and now manifests as Mare. It not only has all your earthly communications, but has complete access to your unconscious, your dreams, your wishes and your fears. Government, now dead, haunts the living. It’s unmoored from the material world. It’s everywhere, it gathers up all the information about us and plots our misfortune. Perhaps it seeks revenge for shrinking it to such as small size that it could be drowned in a bathtub.

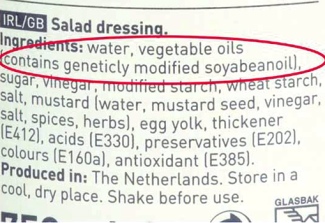

Oddly what we’re complaining about with the issue of privacy is that our “personal data” which is owned by the phone companies, Google, Facebook, Twitter and Microsoft is being given to the NSA. It should be noted that while we call it “our personal data” and “our privacy”, it’s only ours in that sense that it’s corporate-owned information about us. The Network platforms own it. It doesn’t belong to us, we gave it away in exchange for the chance to win valuable prizes. What we fear with regard to the NSA is the standard business model of the technology industry.

You’ve always already been hacked. The use of common protocols has guaranteed there’s no such thing as a secure computer network. At the end of 2010, the head of the NSA noted that the NSA works under the assumption that various parts of their system have already been hacked. They already act like crypto-anarchists and cypherpunks.

Debora Plunkett, head of the NSA’s Information Assurance Directorate, has confirmed what many security experts suspected to be true: no computer network can be considered completely and utterly impenetrable – not even that of the NSA.

“There’s no such thing as ‘secure’ any more,” she said to the attendees of a cyber security forum sponsored by the Atlantic and Government Executive media organizations, and confirmed that the NSA works under the assumption that various parts of their systems have already been compromised, and is adjusting its actions accordingly.

John Poindexter was trying to find the signal through the noise. He was trying to do what Jeff Jonas said was impossible. Jonas said you needed to start with the bad guy and then assemble the data around that point. Poindexter created “Red Teams” to devise terrorist strategies, and then based on the interaction patterns the strategies revealed, the analysts would look for matching patterns in the data. Early tests resulted in a lot of false positives. But that was ten years ago, Big Data has come a long way since then. When TIA was de-funded and removed from the official budget, the systems moved to dark funding and we lost a lot of visibility. The secret system became a secret to the extent that there can be secrets anymore.

Do we still want to try and discern the weak signal through the noise? The editor of Slate.com, David Plotz argues that we’re no longer facing terrorist threats and therefore these security programs are overreach. A position that must be much easier to take if you don’t receive daily intelligence briefings. The amount of noise is ever increasing, the question we need to answer is whether it’s really possible to detect a weak signal. Can you really see into the future with a reasonable probability? If not this way, then how?

Comments closedThe Overload

By Talking HeadsA terrible signal

Too weak to even recognize

A gentle collapsing

The removal of the insidesI’m touched by your pleas

I value these moments

We’re older than we realize

In someone’s eyesA frequent returning

And leaving unnoticed

A condition of mercy

A change in the weatherA view to remember

The center is missing

They question how the future lies

In someone’s eyesA gentle collapsing

Of every surface

We travel on the quiet road

The overload