Arts organizations and charities swallowed hard when they looked at the fine print of President Obama’s budget. Tax deductions on charitable donations from the wealthy are to be further limited in the new plan. The New York Times reported on the ire of the charity industry.

Under the administration’s proposal, taxpayers earning more than $250,000 will have their ability to deduct contributions to charities reduced to a rate of 28 percent from a rate of 35 percent, according to an analysis by the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations.

Professional fundraisers, while concerned, took a different view:

“Research has shown again and again that for major donors, taxes are at the bottom of their list of reasons why they make these gifts,�? said Margaret Holman, a fund-raising adviser in New York. “They make these gifts because they love, are intrigued by, want to invest in their favorite charities.�?

Most, if not all, of our country’s museums, symphonies, regional theaters and opera companies depend on the generosity of large donors. In this severe economic downturn large arts organizations have also seen a sharp reduction in the income generated by their endowments. And as people cut back on their expenditures, the sale of season’s and individual tickets will fall as well. While we focus on the nation’s banks and core industries, there’s a lot of collateral damage being done to our cultural institutions and working artists.

While there’s no such thing as a contribution limit for charities and the arts, one can’t help but compare their predicament with the campaigns of presidential candidates. Historically, winning campaigns have attracted the support and contributions of large donors. This is a continuation of a patronage model that is deeply rooted in the political economics of our history. The largess of the few was the only method of raising the significant sums of money required to run a national political campaign or a major arts organization.

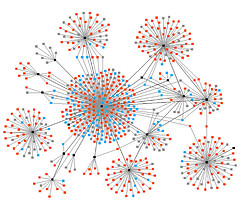

The Obama presidential campaign changed the equation. By reaching out to everyone, employing the Network and lowering the cost of managing a very large number of small donations, Obama was able exceed the results of the traditional fundraising model. A simple way to think of it is to imagine the size and complexity of the social graph of the McCain campaign compared to the Obama campaign. The math is pretty simple, to raise equal amounts of money– how much, on average, needs to come from each node on the network?

To some extent, public broadcasting follows the model of casting a wider net with their pledge drives. The problem is that this method of fundraising is widely perceived as annoying and unpleasant. Donations are often simply made in exchange for bringing the pledge drive to a close. We pay our public broadcasters to stop dragging their fingernails across a blackboard and return to regular programming.

As the business models for public and private broadcasting (including newspapers) begin to converge, we are in dire need of some innovation in how funds are raised. Doc Searls has shown us one possible future with his PayChoice program.

PayChoice is a new business model for media: one by which readers, listeners and viewers can quickly and easily pay for the goods they use — on their own terms, and not just those of suppliers’ arcane systems.

The idea is to build a new marketplace for media — one where supply and demand can relate, converse and transact business on mutually beneficial terms, rather than only on terms provided by thousands of different silo’d systems, each serving to hold the customer captive.

At minimum an opportunity needs to be provided to donate after a great experience with an organization, as opposed to donating to make a bad experience stop. PayChoice is trying to make donations a user-initiated event– where value is paid for when it’s experienced. Needless to say, it’s easier to imagine complex systems than it is to lay down the pipes that would allow those kinds of transactions to flow.

In this era of transformation, arts organizations will need to examine their social graphs and the quality and frequency of the events transacted through them. They’ll need to decide whether they consider social media to be a mere toy, or the foundation of their future.

While we’ve been waiting for the convergence of media devices, we haven’t noticed that the media itself has already converged. We are all broadcasters now, whether in live performance or live over the Network. The potential points of connection have multiplied greatly, but remain largely unused and unappreciated. Just as Barack Obama’s campaign was able to connect and activate a very large network and benefit from those economics– arts organizations, and many businesses, will need to execute the same maneuver. Our relationships just got a little more complicated: they’re connected through the Network in real time, time-shifted, two-way, mobile and always on. The times they are a changing.

Comments closed