I’d like to take something Clay Shirky said out of context. First of all, here’s the context from which I’m going to extract the quote: Shirky gave a talk to a group of journalists about the forward visibility of what he calls “Accountability Journalism.” There are a couple excellent posts on Shirky’s talk by Ethan Zuckerman and David Weinberger. Both are highly recommended reading. The bottom line seems to be that while Shirky, at least, is beginning to be able to articulate why newspapers, as a media type, are unsustainable— visibility into the method by which “accountability journalism” will perdure is very limited. Listening to the Q&A after the talk brought to mind a song by Aimee Mann.

Oh, better take the keys and drive forever

Staying won’t put these futures back together

All the perfect drugs and superheroes

wouldn’t be enough to bring me up to zero

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

couldn’t put baby together again

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

couldn’t put baby together againAimee Mann

Humpty Dumpty, from the album Lost in Space

The journalists in attendance continued to sift through the pieces of egg shell looking for the formula that will put it all back together. I imagine them watching Shirky closely for some signal that pay walls or micro-payments just might be the glue for pieces they’ve been left holding.

Shirky makes clear that he values what “accountability journalism” provides— investigative journalism that holds people, corporations, governments and other institutions accountable for their actions is a crucial function in a democratic society. However, the notion that only newspapers, or news organizations, as they are currently constituted, can fill that need fails to heed the lessons of history.

And while the thread of this discussion is extremely important, I was taken off track by a phrase thrown out by Shirky in the middle of supporting one of his points. And this is where I’d like to remove this sentence from its context and treat it as a standalone fragment. It addresses the mechanics of distribution in space and name space:

“Syndication doesn’t make sense in the age of the URL, as AP has figured out, which is why they’re driving people towards their own content.�?

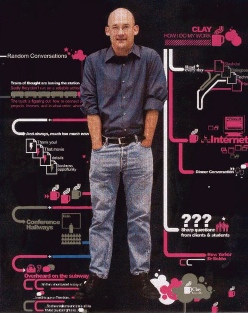

Clay Shirky

in a talk to the Shorenstein Center

for the Press, Politics and Public Policy

The business of syndication is distributing copies of material to non-overlapping localities in physical space. Something produced for one locality can be leveraged into new markets for the cost of sales and distribution. Electronic distribution changed the economics and size of addressable markets substantially. The mechanisms of redistribution generally take the form of local newspapers, television and radio stations. In order for the model to work, there must be a high barrier to entry for local redistribution endpoints.

The qualities of physical space— distance and nearness are the medium through which syndication operates. As McLuhan notes, under electronic information conditions, everything changes. Once there’s a shift from physical space to name space, the concept of distance evaporates. When the Network is the distribution channel, what’s the difference between remote distribution and local distribution? Access via URL obviates syndication, distribution is direct. There’s no business model for local redistribution of remotely produced media product.

It’s interesting that we model physical syndication in technical formats like RSS. Media content is transported from an originating production facility to remote reading machines. The sales proposition is a reversal of transportation energy. Rather than you expending energy “going” to a news source, the news source expends energy “pushing” the news to you. News distribution takes the form of file transfer from over there to my local computer. The value of the pushed news stream is in the editorial decisions around feed subscription. There’s no item level granularity, so while the aggregation of feeds is a substantial advance, it’s only in “shared item” feeds that we start to see the possibility of filtering tools to produce high value synthetic feeds.

The URL, the hyperlink, has allowed readers to tear up the New York Times and share the interesting parts through multiple messaging buses. As Shirky notes, the publication is reassembled on the demand side. This feed of high-value items doesn’t require transport of the items from here to there. In a broadband environment, a playlist of URLs (tweets) delivers the news without moving an inch.

When we use the metaphor of physical space to think through economics of a name space, we end up like the journalists staring at Clay Shirky looking for a sign that everything is going to be all right.

You can read a transcript here or listen to Clay Shirky’s talk here: Clay Shirky on Accountablity Journalism

One Comment