![]()

The rebellion against hyper-targeting continues. Doc Searls weighs in, as does Jason Calacanis. Targeted marketing always worked with fairly crude tools, and because of this it was tolerable. Marketers looked at demographics and psychographics, made educated guesses about the audiences of particular radio or television programs, and did the best they could. It was more art than science. The direct marketers were the most statistically driven. Marketers dreamed of knowing enough to target perfectly. Now with Facebook and other social networks, they’re starting to get their wish. The user inhabits a panopticon, and the data generated belongs to the system to be rented to the highest bidder.

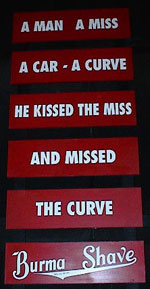

Will the inmates rebel and demand the authority to selectively release data to the system? Will they be able release none of their data and still participate in the system? Can they withdraw their data, move it and use it to their advantage in another system? When a customer uses her data to her advantage in a system, the system benefits as well.The coarse targeting of marketing has required high frequency bombardment. We’re entering the age of smart bombs, but the frequency seems to be just as high. Shouldn’t smart marketing just be the thing I want, when I’ve indicated I actually want it? Advertising frequency goes down, but the number of transactions probably increases.

Comments closed