“If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything; it is open to everything. In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.”

In sorting through the coverage of Apple’s iPhone 3.0 software announcement as it dribbled in through the refreshes and streams of the various tabs on my web browser, I returned to the thought that the iPhone both is, and is not, a telephone. This major upgrade to the operating system had little or no new information about the telephonic capabilities of the device. And the connaisseurs of the mobile telephone often tell me that the iPhone really isn’t a very good telephone. Still, the upgrade to 3.0 brings some significant new possibilities for this device, whatever it might be:

- Cut, Copy and Paste

- Push Notification via Apple’s relay cloud

- Peer-to-Peer wireless connectivity among iPhones

- Programming interfaces to iPhone Accessories (Medical, etc.)

- Access to Core Location within Applications

- Spotlight-style search

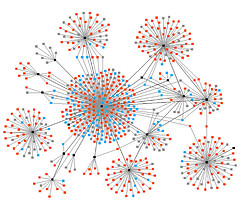

- In application follow-on purchasing

Those who stand by and compare the iPhone’s feature/function set to other mobile phones will complain there’s not much new there. In some form or another, all of these things exist on other phones. Here’s where I have to return to my thought that the iPhone is a phone that isn’t a phone; to the idea that it’s a closed device that is more open to both existing and potential connections than many open devices, that it’s created a vibrant ecosystem with a fully-functioning economy where none existed before. That apples and oranges can be compared, but how fruitfully?

To explore this idea I went back through some interviews given by Steve Jobs and created a mashup. Here’s my imaginary interview with Steve Jobs, where I ask him from a product design perspective what it means to ‘rethink’ the activity of using a telephone; about the importance of software in the integrated design of the post-pc consumer device; and why the iPhone, and not the computer, will be the vehicle of the most radical change in the augmenting of human capabilities through networked computing.

“There’s a phrase in Buddhism,”Beginner’s mind.” It’s wonderful to have a beginner’s mind.”

***

“I don’t want people to think of this as a computer, I think of it as reinventing the phone.�?

***

“Things happen fairly slowly, you know. They do. These waves of technology, you can see them way before they happen, and you just have to choose wisely which ones you’re going to surf. If you choose unwisely, then you can waste a lot of energy, but if you choose wisely it actually unfolds fairly slowly. It takes years.”

“One of our biggest insights [years ago] was that we didn’t want to get into any business where we didn’t own or control the primary technology because you’ll get your head handed to you.”

“We realized that almost all – maybe all – of future consumer electronics, the primary technology was going to be software. And we were pretty good at software. We could do the operating system software. We could write applications on the Mac or even PC, like iTunes. We could write the software in the device, like you might put in an iPod or an iPhone or something. And we could write the back-end software that runs on a cloud, like iTunes.”

“So we could write all these different kinds of software and make it work seamlessly. And you ask yourself, What other companies can do that? It’s a pretty short list. The reason that we were very excited about the phone, beyond that fact that we all hated our phones, was that we didn’t see anyone else who could make that kind of contribution. None of the handset manufacturers really are strong in software.”

***

“Design is a funny word. Some people think design means how it looks. But of course, if you dig deeper, it’s really how it works. The design of the Mac wasn’t what it looked like, although that was part of it. Primarily, it was how it worked. To design something really well, you have to get it. You have to really grok what it’s all about. It takes a passionate commitment to really thoroughly understand something, chew it up, not just quickly swallow it. Most people don’t take the time to do that.”

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things. And the reason they were able to do that was that they’ve had more experiences or they have thought more about their experiences than other people.”

“Unfortunately, that’s too rare a commodity. A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem. The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have. ”

***

“Look at the design of a lot of consumer products—they’re really complicated surfaces. We tried make something much more holistic and simple. When you first start off trying to solve a problem, the first solutions you come up with are very complex, and most people stop there. But if you keep going, and live with the problem and peel more layers of the onion off, you can oftentimes arrive at some very elegant and simple solutions. Most people just don’t put in the time or energy to get there. We believe that customers are smart, and want objects which are well thought through.”

***

“I’m actually as proud of many of the things we haven’t done as the things we have done. The clearest example was when we were pressured for years to do a PDA, and I realized one day that 90% of the people who use a PDA only take information out of it on the road. They don’t put information into it. Pretty soon cellphones are going to do that, so the PDA market’s going to get reduced to a fraction of its current size, and it won’t really be sustainable. So we decided not to get into it. If we had gotten into it, we wouldn’t have had the resources to do the iPod. We probably wouldn’t have seen it coming.”

***

“Well, Apple has a core set of talents, and those talents are: We do, I think, very good hardware design; we do very good industrial design; and we write very good system and application software. And we’re really good at packaging that all together into a product. We’re the only people left in the computer industry that do that. And we’re really the only people in the consumer-electronics industry that go deep in software in consumer products. So those talents can be used to make personal computers, and they can also be used to make things like iPods. And we’re doing both, and we’ll find out what the future holds.”

***

“I know, it’s not fair. But I think the question is a very simple one, which is how much of the really revolutionary things people are going to do in the next five years are done on the PCs or how much of it is really focused on the post-PC devices. And there’s a real temptation to focus it on the post-PC devices because it’s a clean slate and because they’re more focused devices and because, you know, they don’t have the legacy of these zillions of apps that have to run in zillions of markets.”

“And so I think there’s going to be tremendous revolution, you know, in the experiences of the post-PC devices. Now, the question is how much to do in the PCs. And I think I’m sure Microsoft is–we’re working on some really cool stuff, but some of it has to be tempered a little bit because you do have, you know, these tens of millions, in our case, or hundreds of millions in Bill’s case, users that are familiar with something that, you know, they don’t want a car with six wheels. They like the car with four wheels. They don’t want to drive with a joystick. They like the steering wheel.”

“And so, you know, you have to, as Bill was saying, in some cases, you have to augment what exists there and in some cases, you can replace things. But I think the radical rethinking of things is going to happen in a lot of these post-PC devices.”

***

“There’s a phrase in Buddhism,”Beginner’s mind.” It’s wonderful to have a beginner’s mind.”

-30-