We've yet to come to terms with how musicians are paid, on a per stream basis, by the big streaming platforms. Suddenly news comes from Amazon that they are set to pay self-published authors as little as $0.006 per page read. Longer books may receive a slightly higher payment rate.

If one had the goal of stopping writers from writing for e-book publication, or stopping musicians from creating music for the recorded music format, this would be a good strategy. It's hard to imagine another industry that would tolerate this kind of economic contract. If I only eat half of my meal in a restaurant, I expect to pay half price. If I drive my car less than other drivers, I should pay a lower price. If I buy something from Amazon and grow bored with it after a week, I shouldn't have to pay full freight.

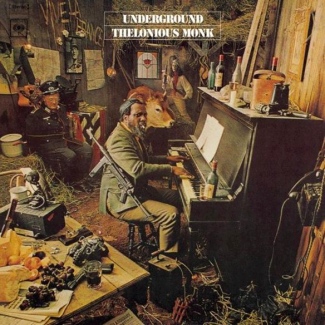

Following in the steps of the band Vulfpeck and their album “Sleepify.” I shall self-publish an Amazon e-book with only twelve blank pages. “Sleepify” consisted of ten 30 second tracks of silence. The band encouraged its fans to play the album on a loop while they slept. Funds raised through this method were used to finance a free concert tour by the band. Spotify owed the band $20,000 in royalty payments and eventually paid up. They then pulled the album citing violations of various policies.

Readers, set your library of self-published e-books to auto-advance and loop. After all I have machines that read all my books for me these days. All I need to know is whether I liked it or not, and a few bon mot for cocktail party conversation.

This is what passes for innovation these days.

Comments closed