It’s not disruptive and it isn’t revolutionary. That’s what’s happened to technology and the Network. The early days of the Internet were filled with promise. The possibilities were endless. People said similar things about television. A short time later TV was described as a vast wasteland. What seemed to make the World Wide Web different was the idea that anyone could publish to the system. Individuals were equal nodes on the Network and that difference would create a force of radical democratization.

Instead the Internet turned into another platform play. Some said the Network was a platform without a vender, and that’s sort of true. But once the World Wide Web became a mass medium, it necessarily became a platform with a small set of vendors. In 2012, Bruce Sterling said the Internet was over and we’d entered “the age of the Stacks.” Platforms are technology stacks, or as the vendors themselves like to position them “ecosystems.”

Real-time social networks radically simplified the publishing process. Type into a “textarea” and click a mouse button to publish. Streams of short messages are arranged in reverse chronological order via non-reciprocal social graphs (subscriptions). To enable instant publication to any other node on the graph, a central hub was required. Structurally this is similar to the way real-time stock quotes work. Transactions are submitted to the central exchange and then broadcast to subscribers.

Owning the hub means owning the platform. When an individual writes into a platform, it means that someone else (a public corporation) owns both the pen and the paper. No individual message has value, but the data generated by the firehose of messages has a high value to advertisers. Despite the millions or billions of users of social media, the possibility of generating revenue is reserved for the few thousand who own and/or work for the platform. It’s not even a pyramid scheme. We need to disabuse ourselves of the notion that services provided by platforms are “free.”

The central hub has visibility into all the messages flowing through the network. Individual subscribers only have visibility into their subscriptions set. It works the same way with search engines. Unless you know the address in advance, you can’t find anything on the World Wide Web. It’s not like entering a library and walking up and down the aisles looking at titles. You can only see what the search engine shows you. The search platform indexes the World Wide Web, the user can only access what’s in the index, the Web is never accessed directly. This is why Sterling talks about Stacks rather than the Internet.

These days to call something disruptive or revolutionary it must disrupt the hub / platform / cloud structure. Creating a new stack or displacing an old stack isn’t disruptive, it’s business as usual. Usenet, established in 1980, has a much more radical structure than any of the dominant Stacks. Even the old BBS systems are more interesting than the central hub model.

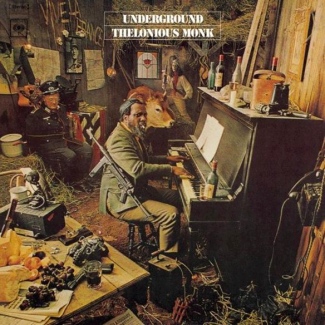

The Network has to go underground. It may even have to go offline, slow down and get much smaller. Most importantly it’ll have to learn how to earn a living outside of the Stacks.