“Design is preserving ambiguity.” This fragment recently surfaced and won’t leave my current playlist. It was a thought expressed by Larry Leifer in a talk called “Dancing with Ambiguity, Design Thinking in Practice and Theory. ” Today it finally collided with a blog post on StopDesign.com. Douglas Bowman is leaving Google, where he was employed as a visual designer. He summed up his reason thusly: “I won’t miss a design philosophy that lives or dies strictly by the sword of data.”

Our human interactions with the Network swim in a sea of data. Each stroke of a key or click of a mouse leaves a trace somewhere. The business of analyzing these traces to plot the trajectory of our activity streams powers the internet economy. And while past performance is no guarantee of future results, it’s apparently close enough.

This begs the question that was asked of Mr. Bowman. If design and ambiguity are intimately intertwined, can ambiguity be preserved through the sword of data? In this particular skirmish, the answer appears to be no.

Ambiguity is the enemy of economics in the Network’s current equation. The ratio of clarity to ambiguity must always be advancing in favor of clarity. Value is equated with unimpeded visibility, its end goal a kind of panopticon. What then of poor ‘ambiguity?’ — linked in this context to the opposite of value. In the grips of such an economy, why should ambiguity be preserved?

If design has value, then ambiguity must have value. What, then, is the nature of the value of ambiguity? A thing that is ambiguous may have more than one meaning, and may have many meanings. Proponents of logic would have us push ambiguity in the direction of nonsense.

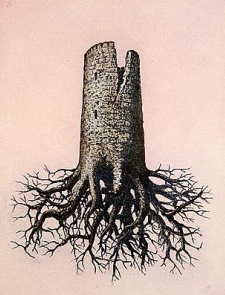

But we can also move in the direction of the dream and poetical thinking. The design object is overdetermined, overflowing with meaning. It connects with the emotions of each individual and the diverse set of circumstances that are linked to those emotions. Imagine a graph linking the design object to the emotions of each person and then the circumstances that provided the ground for those emotions.

Clarity produces value in a restricted economy, in a controlled vocabulary. Ambiguity produces value in a general economy, in a language open to play. Just as with clarity, not all ambiguity is created equally. The poet’s pen, the designer’s pencil, the painter’s brush make the clear mark that overflows with meaning.

Of course these thoughts have been batted back and forth over the tennis net for years upon years. Ambiguity continually undervalued, the underdog, beaten at every turn, it continues to limp along. Although, never fully disposed of, for to get to where you’ve never been, there is no clear road. To see what you’ve never seen requires a different kind of vision.

From T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets:

You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not.