There’s little point in asking whether the leaks are pro or con: the bell has been rung, the horse is out of the barn, the cat is out of the bag. Once the bits in question have been linked to the Network they exist everywhere at once. The inside is out. Its effect is much like that of ice nine.

The event signals a change. The Network is now pressing up against every utterance, every written or encoded communication. The membrane between the Network and our conversations has become paper thin. Here we begin to have conversations as though we live in a surveillance state. We look for the remaining shadows, the out-of-the-way corner, the crevice where we’re out of earshot of the Network.

We had a sense that the Network was a neutral medium, open and free to all comers. No one knew you were a dog, and you didn’t need much at all to publish to the whole web of the world. But there’s a difference between the ability to publish and the absolute transparency implied by the leak. No doubt there’s someone somewhere who feels they have a right to secrets you’ve been keeping to yourself.

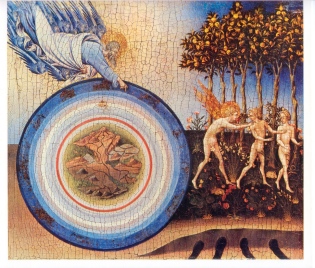

Some bits have been flipped, what was confidential within a trusted circle is now in general circulation. The opaque is now transparent. But something more than that happened. The disclosure was an exercise of power, it had a real impact in the world. It was a military exercise, a wall has been breached, a boundary overcome. The force of those bits being flipped was felt like a punch in the face. Power was awakened and has been loosed upon the Network. Active countermeasures are an effective means of defending a breached border. We have been ushered out of the garden, and now are filled with the knowledge of good and evil. Power travels along many paths, not all of them in the bright sunlight.

The concert at Yasgur’s farm near Woodstock was held from August 15 – 18, 1969. About 4 months later, the Altamont Speedway Free Concert was held on December 6th, 1969.

The theory is that the targeted system can be paralyzed by causing trusted internal message circulation to be severely limited. The power of the Network can be used to cause a hardening of the arteries. When no member of the system can trust any other, the system ceases to function unless it embraces absolute transparency. Of course any system that attacks another system with this method is subject to the same treatment. And although we might say this new method of disclosure is without a home in a nation state, that doesn’t mean it lives entirely in the ether of the Network— it has plenty of earthly bounds and connections. The structure of the Network will provide a limited amount of protection, or rather it provides camouflage for both armies. It should be remembered, there’s a substantial difference between winning an argument and winning.

The dilemma is that to preserve a ‘free and open’ Network, we must preserve the possibility of evil. And where we once thought the walled garden was an uncalled for limitation on our freedoms, we may soon be seeking its protection.

New Speedway Boogie

Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia

One CommentNow I don’t know but I been told

it’s hard to run with the weight of gold

Other hand I heard it said

it’s just as hard with the weight of leadWho can deny? Who can deny?

it’s not just a change in style

One step done and another begun

in I wonder how many miles?Spent a little time on the mountain

Spent a little time on the hill

Things went down we don’t understand

but I think in time we willNow I don’t know but I been told

in the heat of the sun a man died of cold

Do we keep on coming or stand and wait

with the sun so dark and the hour so late?You can’t overlook the lack Jack

of any other highway to ride

It’s got no signs or dividing lines

and very few rules to guide