The first time I heard the phrase it was used to describe something that happened at Johnny Cash’s house in Hendersonville, Tennessee. As the story goes, it was February of 1969, the hour turned late and the party at Cash’s house turned into a guitar pull. Bob Dylan sings “Lay Lady Lay”, Joni Mitchell sings “Both Sides Now”, Graham Nash sings “Marrakesh Express” and Kris Kristofferson sings “Me and Bobby McGee.” There are no recordings of that evening, or none that have surfaced publicly. We only have the stories and memories of the people who pulled out a guitar and put across a song. Oh to be a fly on the wall.

The “guitar pull” is a tradition that comes from country music. Musicians sit around and take turns playing songs. The origin of the phrase has been lost, its first speakers are time out of mind. Some say that it refers to passing a single guitar around, everyone taking their turn. Not everyone owned a guitar, but everyone had a song to sing. People “took a turn” in the sense of pulling the guitar from someone’s hands so they could get their song out.

Musicians playing on a stage for an audience is the dominant configuration for live performance. Occasionally it’s done in the round, but usually music is presented from within a proscenium — musicians on one side and the audience seated in rows on the other. The guitar pull has a different shape. The musicians and the audience aren’t separate, they aren’t even that different. I imagine the shape as roughly circular — a presentation to each other. This is different from musicians sitting around in a recording studio performing for a microphone. No one’s trying to create the definitive version of a song that will go on to sell millions of copies. In a sense, the purpose of the guitar pull is to keep it going. One song brings another out of the group.

A related way of organizing a performance is Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble. The ramble was a rent party in a barn that held about 200 people. Its purpose was to help save Levon’s house from his creditors and rehabilitate his voice after surgery for throat cancer. The audience brought casseroles for a pot luck dinner and music played late into the night. There’s a scene in Scorsese’s movie “The Last Waltz” where Helm tells a story about the origin of the midnight ramble.

“After the finale, they’d have the midnight ramble. The songs would get a little bit juicier. The jokes would get a little funnier and the prettiest dancer would really get down and shake it a few times. A lot of the rock and roll duck walks and moves came from that.”

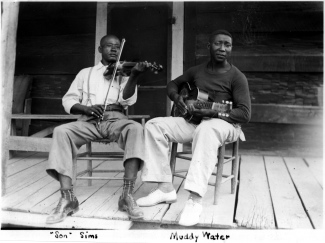

The shows in the barn in Woodstock weren’t really patterned on the midnight ramble so much as the house parties thrown by blues musicians. On Levon Helm’s website, Kay Cordtz writes about Muddy Waters and his pop-up juke joints.

When Muddy Waters was developing his blues style in the 1930s, he would sometimes play for fans and fellow musicians at his house on the Stovall Plantation, transformed into a juke joint of sorts. They’d move the beds outside so people could dance, sell moonshine and run craps tables out back. Muddy would try out new sounds, make a little money, and everybody would have a ball. People told of finding the place in the dark of the country night by the light of hanging coal oil lamps, and hearing the guitars and people hollering through the trees before you got there.

For musicians like Muddy Waters there was a lot of power in having a venue where he could play the music he wanted for a receptive audience. It’s a kind of control that musicians rarely enjoy. That’s what makes Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble a powerful disruption of the music business. And it’s a place that musicians who’ve scaled the heights of pop-music success always seem to be trying to get back to.

“We had to almost invent a place to perform.”

– Levon Helm

“It felt like the house was calling for musicians to come be a part of it.”

– Amy Helm

There’s a small trend emerging among musicians of trying to invent new places to perform. These new places have their roots in the guitar pulls, pop-up juke joints and midnight rambles. On the west coast, Bob Weir built TRI Studios to provide an intimate space to create and broadcast music. But the most surprising and delightful new space has to be Daryl’s House.

In an interview with Peter Lewis, Daryl Hall describes why he started “Live from Daryl’s House”, his monthly web-based music series.

“Well, for me it was sort of an obvious thing. I’ve been touring my whole adult life really and, you know, you can’t be everywhere. Nor do I want to be every-where at this point. I only like to spend so much time per year on the road. So I thought ‘Why don’t I just do something where anyone who wants to see me any-where in the world can?’

And, instead of doing the artist/audience performance-type thing, I wanted to deconstruct it and make the audience more of a fly-on-the wall kind of observer. You know, I actually like the added intimacy of having no audience in the room with us – just the musicians, myself and the crew hanging out, sitting around talking, rehearsing a song, and then just playing it.”

Daryl Hall has created that fly-on-the-wall view into a guitar pull — that view I wish had into Johnny Cash’s living room in February of 1969. Sure, in Hall’s version the arrangements have been worked out and there’s a little rehearsal. But it’s just enough so that talented musicians can pull it off at a pretty high level. It’s not a rote presentation, you can see the song being discovered as it’s being performed. And like a guitar pull, the music is performed for the musicians. As Hall says, there’s an “added intimacy.” The players don’t look at cameras or out at an audience, instead they look at each other. Daryl Hall has been around long enough to know there’s a different sound created in this kind of environment. It’s a sound that musicians love and one that’s really worth hearing.

Here’s Booker T. Jones on the experience of playing at Daryl’s House.

“One of the nicest things about performing on Live from Daryl’s House is that Daryl has surrounded himself with musicians who can ‘hear’ That is, each one has talent to the extent of being capable of performing as a soloist on his own, not needing to be told the proper notes to sing or play.”

Some believe that the future of popular music is Pandora, Spotify, iRadio and Rdio. These services appear to be cutting edge technology. But the reality of these streaming services is they’ve got a defective business model. They can’t afford to pay the musicians who provide 100% of their content. That means ultimately they’ll be serving up music in its last window of freshness. Once a musician has made as much as she can through every other avenue, then the songs can be sent to the streaming services. It’s the equivalent of waiting until a movie comes out on Netflix. Essentially these services are oldies stations.

The technology used to create “Live from Daryl’s House” seems much more cutting edge to me. Even if that consists of a single omni-directional microphone in the middle of the living room and a cable running down the hallway to a recording set up. Like Muddy Waters, many musicians are starting to invent new places to perform. If you want to know where music and technology is going, check out Daryl’s House.