“I’d swear he was the same guy. He was the spitting image.” It’s a saying that speaks of two being as one, and yet being fundamentally different. An apt phrase for the messy business of representing identity. These thoughts are provisional, but have been triggered by pondering the ideas of Internet Identity and the Semantic Web. Any discussion of representation taps into a long historical dialog.

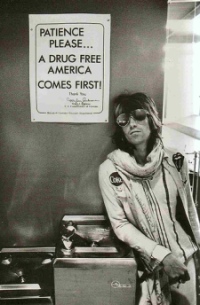

We look to the photograph to clarify, to lift the fog of ambiguity, to testify. Muybridge’s photos settled a bet by revealing the manner in which a horse truly runs. Speaking of the power of photography to capture the image, Susan Sontag said:

A photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image), it is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real, like a foot print or a death mask.

Visual evidence is highly convincing– we say seeing is believing. The voice can testify to the facts of the case. The written word, except for the wet ink signature, is open to many interpretations. But both seem to rely on conveying what is physically seen with the eyes.

On the Network, we try to create a tapestry of unique numerical endpoints– and we assign names to the space so that we may become conversant with it. It’s a supergluing of a signifier to the signified. It’s a kind of attachment that doesn’t happen in natural language. It’s like saying “I mean what I say, and I say what I mean.” It’s the ambiguity in language that lets the future in. A simple way to understand this is to consider a chart in Sean Hall’s book on Semiotics: This Means This, This Means That:

| Signifier | Signified | |

| Apple | means | Temptation |

| Apple | means | Beatles |

| Apple | means | Healthy |

| Apple | means | Fruit |

| Apple | means | Computer |

| Apple | means | Gwyneth’s kid |

| Signifier | Signified | |

| Apple | means | Apple |

| Pomme | means | Apple |

| Apfel | means | Apple |

| Manzana | means | Apple |

The truth value of the table? True in every case, and the size of the table is unlimited. There’s a slipperiness to language that allows a play of meaning across a field of usage.

A namespace relies on coordinates in space as opposed names and language. We claim a name in a particular space to take it out of circulation. We preserve its uniqueness with technology and the law. As we apply Occam’s Razor across the technology of the Network, we might think about where we can allow the signifier to play freely.

For instance what if your display name (not your login name or your opaque database key) on a social network didn’t have to be unique or even singular? What if it was identifiable through its relationships, connections, geography, avatar, and activity streams? Allow the messiness of the world to be mirrored in the messiness of the Network. In the wild, Identity isn’t created through unique identifiers, but rather through the intersection of different lines of activity flows through time– the collection of differences. Or as Saussure calls them a system of difference. Laclau explores the idea a bit more:

We know, from Saussure, that language (and by extension, all signifying systems) is a system of differences, that linguistic identities, -values – are purely relational and that, as a result, the totality of language is involved in each single act of signification. Now, in that sense, it is clear that the totality is essentially required – if the differences did not constitute a system, no signification at all would be possible. The problem, however, is that the very possibility of signification is the system, and the very possibility of the system is the possibility of its limits. But if what we are talking about are the limits of a signifying system, it is clear that those limits cannot be themselves signified, but have to show themselves as the interruption or breakdown of the process of signification. Thus we are left with the paradoxical situation that what constitutes the condition of possibility of a signifying system – its limits – is also what constitutes its condition of impossibility – a blockage of the continuous expansion of the process of signification.

In the technology of language and the language of technology, we imagine a kind of systematic extensibility that can capture meaning and the play of signification in real time. But can it?

Comments closed