As the ‘RSS-is-fast-enough-for-us’ crowd begins to resemble the Slowskys from the television commercial, an effort has begun in earnest to speed up the transport of RSS/Atom feeds in the face of real-time media. These efforts will answer the question about whether RSS is structurally capable of becoming a real-time media. If the answer is yes, then RSS will become functionally the same as Twitter. If the answer is no, then it will become the rallying point for the ‘slow-is-better’ movement.

There’s a strong contingent who will say that more speed is just a part of the sickness of our contemporary life. We need to ‘stop and smell the roses’ rather than ‘wake up and smell the coffee.’ And while there are many instances in which slow is a virtue, information transport isn’t one of them. Under electronic information conditions, getting your information ‘a day late’ is probably why you’re ‘a dollar short.’

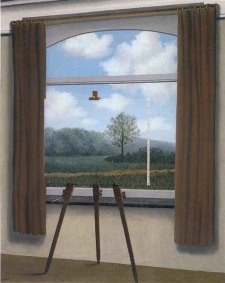

When you begin thinking about the value resident in information, it’s instructive to look at the models of information discovery and use on Wall Street. Analysts generate information about companies in various investment sectors through quantitative and qualitative investigation. The high-value substance of the reports is harvested and acted upon before the information is released. High value information lowers transaction risk. Each stage of the release pattern traces the dissemination of the information. Within each of these waves of release, there’s an information arbitrage opportunity formed by the asymmetry of the dispersion. By the time the report reaches the individual investor—the man on the street, it is information stripped of opportunity and filled with risk.

In Friday’s NY Times, Charles DuHigg writes about the relatively new practice of high-frequency trading. Under electronic information conditions, the technology of trading moves to match the speed of the market.

In high-frequency trading, computers buy and sell stocks at lightning speeds. Some marketplaces, like Nasdaq, often offer such traders a peek at orders for 30 milliseconds—0.03 seconds—before they are shown to everyone else. This allows traders to profit by very quickly trading shares they know will soon be in high demand. Each trade earns pennies, sometimes millions of times a day.

If you were wondering how Goldman Sachs reported record earnings when the economy is still in recession, look no further than high-frequency trading. The algorithmic traders at Goldman have learned how to harvest the value of trading opportunities before anyone else even knows there’s an opportunity available. By understanding the direction a stock is likely to move 30 milliseconds before the rest of the market, an arbitrage opportunity is presented. High-frequency traders generated about $21 billion is profits last year.

Whether you think the real-time web is important depends on where you choose to be in the release pattern of information. If you don’t mind getting the message once it’s been stripped of its high-value opportunity, then there are a raft of existing technologies that are suitable for that purpose. But as we see with the Goldman example, under electronic information conditions, if you can successfully weight and surface the opportunities contained in real-time information, you can be in and out of a transaction while the downstream players are unaware that the game has already been played.

Creating an infrastructure that enables speed is only one aspect of the equation. The tools to surface and weight opportunities within that context is where the upstream players have focused their attention. And while you may choose not to play the real-time game, the game will be played nonetheless.

6 Comments