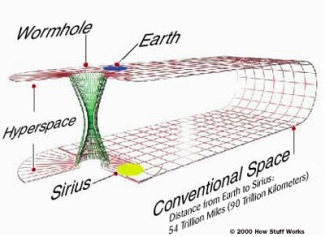

It’s as though we just looked up and noticed that someone is watching us. It’s that creepy feeling. You know that someone or something sees you, but you can’t see them. The Internet seemed like a place where no one knew whether you were a dog or not. Identity didn’t matter and that’s what created a level playing field, a kind of equality. But then it turned out that you could be identified, that you identified yourself on social networks for fun and profit, that your identity information and preferences could be aggregated and sold without your knowledge. Rather than a casual conversation, the Internet turned into an indexed and searchable permanent record. It’s the equivalent of having everything you type into your network-connected keyboard published to the front page of USA Today in real time. And that’s a very strange context in which to speak.

Doc Searls recently weighed in on the issue of Privacy in the age of connected digital networks. It’s an issue that he’s been deeply involved with for many years. Much of our current dilemma could be seen coming from a mile away. But here’s why Doc sees this as a pivotal moment:

I see two reasons why privacy is now under extreme threat in the digital world — and the physical one too, as surveillance cameras bloom like flowers in public spaces, and as marketers and spooks together look toward the “Internet of Things” for ways to harvest an infinitude of personal data.

There’s a joke that Marc Maron tells: “Big Brother is watching us. That’s what we pay him for.” Maron gets to the conflict at the heart of our complaint about surveillance. In a sense, this is what we’ve asked for. We want maximum safety and so we authorize and pay for unlimited surveillance in the hopes of preventing catastrophic events. Now that we see how our wishes are being carried out, we’re troubled — isn’t total information awareness just for the bad guys? Be careful of what you wish for…

Marshal McLuhan called advertising our cave art. It expresses our most basic desires. Some would say that it creates them, but the truth is that the desire needs to be there to start with. Advertising calls that deep desire to the surface. There’s a television ad that’s running now that says a great deal about who and what we’re thinking right now. It’s for a car called the Infiniti Q50.

We see a “Factory of Life”. Men and women, young white professionals are being assembled and outfitted in a factory. A disembodied voice narrates the stages of the process. Industrial robots apply lipstick to the women’s lips. The men’s suit coats and ties are fitted with precision. All the personal style is very high end — but it’s all identical. Industrial capitalism has raised the standard of living to a level of luxury. There are no workers in the factory, there are only the people on the assembly line getting a commodified wealthy lifestyle. Either the people of color are being hidden behind the walls of the factory or the factory has remanufactured their ethnicity to conform to a pre-established standard.

As our hero moves down the assembly line, it becomes clear that this isn’t a socialist utopia where everyone can enjoy the benefits of wealth. It’s a surveillance state where conformity is strictly enforced. Everyone accepts what’s happening to them with a blank stare. There are no emotions — merely impeccably-dressed cogs in the machine. No one loves the artifacts of their wealth, no one enjoys the luxury.

A robot arm puts our protagonist’s necktie into place and he experiences a sudden spark of consciousness. He turns and sees his reflection in some glass. He smiles, thinks “I look pretty good.” As he looks around, suddenly he’s able to see the Matrix. He moves farther down the assembly line to where car keys are being distributed. The keys are to identical C-class cars by Mercedes Benz. Each figure takes a key without complaint. We can see that our hero has begun to question what’s going on. A woman’s face appears on a small screen that only he can see. She’s a human like him and she’s hacked into the Matrix to help get him out. She tells him to check his pants pocket for a set of keys. These are the keys to the Q50 and escape from commodification and conformity. He takes the keys and makes a run for it.

The surveillance system detects his his break from the assembly line and dispatches robots to capture or possibly kill him. He’s not pursued by humans, it’s only technology that enforces its own mechanistic repetition. Making a different choice is clearly a dangerous act. The mechanical forces of commodity chase him as he makes his way to the Q50. He gets in, starts it up and drives out of the factory. The robots engage in the chase, but are left in the dust. The Q50’s acceleration is fantastic and quickly the factory recedes in the distance. The road opens in front of him as he drives out of the darkness and into the light. Freedom.

We easily forget that a commodity with special sauce provides our hero with the means to escape the boring commodities that everyone else accepts. A commodity provides the escape from commodity. It’s an open question how he will make a living outside the machine. No doubt he will live by his wits. The “Factory of Life” that opens the commercial is a good representation of what we’re asking of technology. It’s an expression of our wishes and desires. The machine will supply us with the good life as long as we accept the conformity and don’t get out of line. “Assimilation is beauty.” Individual desires can’t be tolerated. There’s great wealth for everyone in the envelope of a surveillance state. Not unlike the way we trade our personal data for a wealth of free online services.

And predictably, we want to view ourselves as the individual who breaks out of the mold. We’re not part of the machine, we have free will and a need to express our individuality. We wake from a dream anchored to one set of commodities and a mechanized life into another dream level where a revolutionary set of commodities anchor a new and improved fantasy with 30% more freedom. You and I wake up to see that we’re in a surveillance state of cloud computing and the NSA. We see our reflection in the glass and enter Lacan’s mirror stage. We perceive the image of our body and form a mental image of our individual identity. We make a run for it. We’ll live by our wits.

The idea of the “mirror stage” is an important early component in Lacan’s critical reinterpretation of the work of Freud. Drawing on work in physiology and animal psychology, Lacan proposes that human infants pass through a stage in which an external image of the body (reflected in a mirror, or represented to the infant through the mother or primary caregiver) produces a psychic response that gives rise to the mental representation of an “I”. The infant identifies with the image, which serves as a gestalt of the infant’s emerging perceptions of selfhood, but because the image of a unified body does not correspond with the underdeveloped infant’s physical vulnerability and weakness, this imago is established as an Ideal-I toward which the subject will perpetually strive throughout his or her life.

There’s a common political move that allows the complainant to achieve a state of blameless innocence. “Since I completely disagree with what the government is doing; I therefore bear no responsibility for its actions. It’s those people, not me who are doing this terrible surveillance. I am innocent; they are guilty. Me good, world bad. My purity remains as pure as it ever was.”

When things are going well, we’re quite proud of the idea of government by the people, for the people and of the people. In the experiment called the United States, the actions of the government are the actions of the people. The President is President of all of the people, not just those who voted for him or her. Instead of declaring our absolute innocence with regard to the bad acts committed by our government, what if we took personal responsibility for them. Those are our dreams and desires manifesting in the real world. Yes, those bad acts were committed in my name. And that defines my morality and the morality of my fellow citizens. We do that. We asked for, and paid for, a surveillance state. It’s only by owning it that it can be changed.

Comments closed