“Technology is at its best when it gets out of the way. Good technology blends in.” Most of the top technology firms take these ideas as their credo. This is the way Apple talked about the iPad, and the way Google now talks about their augmented reality appliance, Google Glass. The fact that the highest aim of technological devices is to get out of the way is a clue to how broken technological interfaces and devices have been.

Take Heidegger’s favorite example of the hammer. The hammer blends in, it gets out of the way when we are successfully hammering in a nail. The hammer itself, as a tool, blends into the background of the hammering activity. It’s only when the hammer breaks that it juts back into our world of hammering with its brute physicality as a “hammer.”

Another example used by Heidegger is wearing corrective lenses in the form of glasses. While they appear to be the closest thing, literally resting on your nose — while they are in use, they are the farthest thing from us. They exist in another world entirely.

Google Glass takes an interesting path to the background. The example of the hammer shows us that any tool, whether it contains onboard network-connected computer processing or not, can become a part of the background. Heidegger’s discussion of eyewear tells us something about what is near or far in the context of the person engaged in a project in the midst of the world. Google Glass moves to the background by attempting to move into, or behind, our eyes. Like the example of eyewear, the eye itself is part of the background when it is merely seeing. This technology gets out of the way by positioning itself outside our field of vision and then superimposing augmentation layers on it.

Google’s augmented reality appliance attempts to erase its material presence. Its only trace is the data it projects onto the world. In this sense, it is an metaphysical idealist par excellence. Its camera claims to record the world from a unique subjective perspective. From outside of the world, as it were. Do you see what I see? Well, now you can. Click here.

Of course, while the position of Google’s Glass gets it out of the user’s way, it puts itself directly in everyone else’s way. “Glass” breaks your face for me. It’s no longer operating as a face, now it’s a camera and potentially it’s projecting augmented reality data on or over me. This is the problem with misunderstanding how backgrounds work. Being physically “out of the way” is not the same thing as blending into a background.

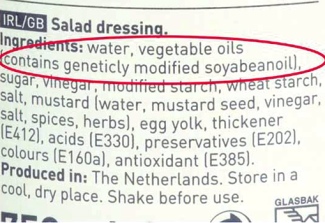

Technology yearns to recede into the background just at the moment when the background itself is broken. Global warming and other forms of pollution have resulted in the geological era known as the anthropocene. The combined force of human activity is now part of what we used to call the background. Extreme weather and other strange events jut out of the background and disrupt the status quo of our everyday world. What they’re telling us is that our everyday world has ended. The background is permanently broken. The narrator no longer inscribes his story on the backdrop (augmented reality); it’s the backdrop that inscribes its narrative onto the narrator. These strange weather events are an augmentation of reality from reality’s point of view.

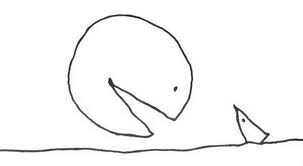

Rather than tools that attempt to blend with background, perhaps we need tools that are partially broken. Tools that are a little weird and occasionally provide unexpected results. Tools that remind us of where they came from and the labor conditions under which they were produced. Tools that start a conversation from the tool-side of the divide. In his letters from the 1940s and 50s, Samuel Beckett writes about his decision to write in French rather than English. He points to:

“le besoin d’être mal armé” (“the need to be ill-equipped”)

Writing in English was starting to “knot him up”, it was a language he knew too well. It was this ill-equipped writer that would one day write “Ill Seen, Ill Said“. In addition to the necessity of using broken tools, Beckett also points another writer with his phrase: Stephane Mallarme. Mallarme was one of the first poets to bring the background into the body of the poem. In his poem “A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance” the white space, the background of the text becomes part of the work. When philosopher Tim Morton talks about “environmental or ecological philosophy” he’s trying to get at just this. It’s not a philosophy that takes the environment or ecology as its topic, but rather a thinking that’s ill-equipped, a little broken, a little twisted, where shards of the background come jutting through.

Google’s Glass is signalling to us about backgrounds and our place in them. It’s a message we can only hear in the moments before we raise the appliance and attach it to our face.