There are a number of narratives located in the words “open source.” The most dominant narrative is the story about software development and maintenance through tightly coordinated iterations via inputs from a potentially unlimited and unbounded number of interested parties. The economics of open source require the diversification of the carriers of value from the traditional modes. I’ve purposefully begun this exploration with economics rather than the concept of free access to source code.

It’s the idea of “free” that has expanded to connect up with other “free narratives” to create confusion. It’s a kind of utopian vision: free beer, free speech, free love, free software. A binary opposition is generated that pits free + generosity against price + greed. The moral elements of the equation rise to the surface when comparing alternative software solutions. There’s a utopian narrative that has attached itself to open source software and simultaneously detached itself from any rational economics. It’s a story of free beer rather than free speech, and is utopian in its original meaning of “no place.”

Chris Anderson has focused the conversation with his forthcoming book called “Free.” The emerging economic model he describes is woven from value transactions across multiple delivery and product modes– some free others at a cost. This blend results in a sustainable economic system. It’s the combined value of the whole set that matters, not the percentage of free delivery modes vs. pay delivery modes. And as we move further into the attention-gesture economy, the methods of payment will be more diversified as well. One-hundred-percent free in all modes, for all time, is simply a method of incurring debt. At some point the system has to come back into balance, either through the addition of a revenue component or bankruptcy. Hobbyist or enthusiast systems work through the attention-gesture economy, but so do services like The Google.

There are thousands of open source projects, but the ones that combine well with commercial projects are the most active and well supported. The number of active projects is actually quite small. Entrepreneurs are constantly searching for new combinations to produce excess value at viable margins. As products become more modular, value migrates to design. Apple’s operating system combines open source infrastructure with a highly-customized human interface. The combination creates superior value.

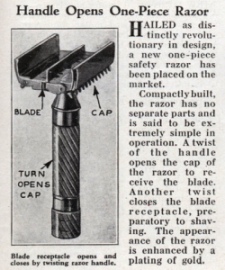

There’s a temptation to believe that all the players in a commercial market should contribute openly to the commons– that we should all come together and sing kumbaya. The fact that every new digital product will contain some form of open source module doesn’t change the competitive landscape. Companies may sing kumbaya, but they still wield the razor and the blade, and that’s as it should be.

6 Comments