I recently heard Doc Searls talk about his interest in developing a method to send money to musicians, radio progams and other forms of streaming entertainment. If you like something, you should be able to show it by putting your money where your mouth is. It’s a thought provoking idea that challenges the underlying fundamentals and economics of a well established industry.

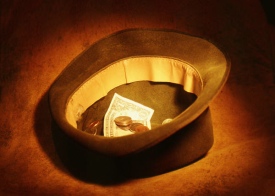

Presumably some kind of name space would need to be developed for the recipients of payments– a URI that could be addressed from a distributed set of listening contexts. The basic idea is that the listener can set the terms of the transaction, in some ways it’s like the traditional tip jar or passing the hat. I’m not clear if the intention is to link to existing micro-payment systems or to develop new ones, but presumably there would be more than one transaction mechanism.

Much like Wikipedia and other social projects, the idea of creating a real economics for musicians based on voluntary payment has been met with skepticism. Kevin Kelly draws the boundaries of the economic system in his post 1,000 true fans. The gist of the contention is:

A creator, such as an artist, musician, photographer, craftsperson, performer, animator, designer, videomaker, or author – in other words, anyone producing works of art – needs to acquire only 1,000 True Fans to make a living.

A “true fan” is someone who will buy everything an artist produces. Obviously to yield 1,000 true fans an artist may need ten or twenty times as many regular fans. Kelly’s post attracted a number of responses, including one Kelly noted from Jaron Lanier:

Jaron claims that he has not found a single musician that meets this definition. In other words, he claims that there are no musicians who have risen to a successful livelihood within the new media environment. None. No musician who is succeeding solely on the generatives I outline in Better Than Free. No musician born digital, and making a living in the new media.

Kelly followed up with two posts: The Case Against 1,000 True Fans and The Reality of Depending on True Fans.

Doc Searl’s proposal would shift the responsibility of developing payment modes from the artist to a payment system. This is a key friction point for artists, they’re good at making music not managing micro-payment systems. But for me, another question emerges: if I like the song “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” what are my payment options?

- The Beatles

- George Harrison

- Eric Clapton, for that guitar solo

- George Martin, as producer

- Prince, for that guitar solo (RRHOF version)

Who owns which part of a performance? Can they be addressed separately? What about multiple versions of the same tune? What about cover versions? Can a performance be addressed as a complex network? Can we make it easy to pull that one thread from the cloth? Is there a viable Buddhist Economics that can emerge from this confluence of efforts?

The framing of a performance contributes to its total value. This would be true of a performance encountered somewhere on a distributed Network as well. Virtuoso violinist Joshua Bell recently played unannounced in a subway station. That venue, as opposed to a concert hall, altered the audience’s perception of the value of his performance.

Joshua Bell made $32.17 as a busker. He commented:

“Actually,” Bell said with a laugh, “that’s not so bad, considering. That’s 40 bucks an hour. I could make an okay living doing this, and I wouldn’t have to pay an agent.”