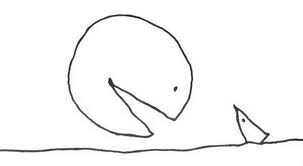

The objects that accumulate around us remain silent and so eventually sink into the background. Once part of the background they are present but completely disappeared. Like fish in water, we swim in this sea of objects. We maintain some kind of interactive relationship with a set of these consumer objects, but due to our physical finitude we can only keep a small number of balls in the air.

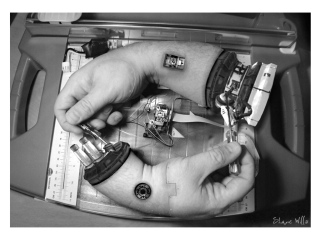

The Internet of things is coming upon us faster than anyone could have imagined. From the large scale “Brilliant Machines” industrial project of General Electric to the personal clouds of SquareTags imagined by Phil Windley and others. It was in Bruce Sterling’s book called “Shaping Things” that I was first introduced to the concept. The little book seemed to call out to me from the shelves of the bookstore at the Cooper-Hewitt.

Things call to us in different ways. The Triangle Shirtwaste Factory fire called out to a generation about the role of labor conditions in the very clothing on their backs. The stitching told a story about conditions under which the stitching itself occurred. Instead of fading into the background, the threads become Brechtian actors employing the verfremdungseffekt.

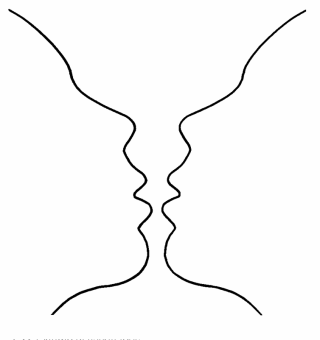

The term Verfremdungseffekt is rooted in the Russian Formalist notion of the device of making strange (Russian: прием остранения priyom ostraneniya), which literary critic Viktor Shklovsky claims is the essence of all art. Lemon and Reis’s 1965 English translation of Shklovsky’s 1917 coinage as “defamiliarization”, combined with John Willett’s 1964 translation of Brecht’s 1935 coinage as “alienation effect”—and the canonization of both translations in Anglophone literary theory in the decades since—has served to obscure the close connections between the two terms. Not only is the root of both terms “strange” (stran- in Russian, fremd in German), but both terms are unusual in their respective languages: ostranenie is a neologism in Russian, while Verfremdung is a resuscitation of a long-obsolete term in German. In addition, according to some accounts Shklovsky’s Russian friend playwright Sergei Tretyakov taught Brecht Shklovsky’s term during Brecht’s visit to Moscow in the spring of 1935. For this reason, many scholars have recently taken to using estrangement to translate both terms: “the estrangement device” in Shklovsky, “the estrangement effect” in Brecht.

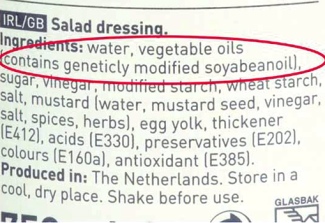

For this generation, the tragic factory collapse in Bangladesh has radically changed the clothing hanging in our closets and folded in our chest of drawers. The stitching and the labels in these clothes now call out, they make themselves strange and unfamiliar. A piece of the background pricks our attention and wants to have a conversation. “Let me tell you about myself. I was born in Bangladesh in a factory like the one you read about the other day on your iPad.”

In the Internet of things, the number of things that could be transmitting data to a central store is limited only by practicality. In other words, it’s practically unlimited. Although, as Lisa Gitelman reminds us “Raw Data is an Oxymoron.” Data is a form of rhetoric based on exclusion. Deciding what counts as data is always already a form of cooking. Drawing conclusions from big data is not making an assessment of big pile of raw, natural artifacts. Data is always pre-cooked and can benefit from an analysis of our counter-transference toward it. And while the Internet of things seems to be mostly on the side of objects helping to manufacture themselves more efficiently, there’s another side to the conversation aspect of the objects surrounding us.

Not too long ago it was our food that was calling out to us. “Ask me where I’m from. Let me tell you about how I was grown.” We’ve been through the whole cycle by now. At first we could hear the words “natural” and “organic” and know something about origins. Today highly-processed foods sport the labels natural and organic. A longer dialogue than can be printed on a container is called for. Now our clothes need to explain themselves. We need to be able to ask them about where they were stitched up, and they need to be able to tell us.

In Bruce Sterling’s “The Last Viridian Note” he makes the case for deaccessioning one’s collection. If we are all curators, defining ourselves by exhibiting our taste as consumers — what are we saying about ourselves? And in this era of the Internet of things, what will the things themselves be saying about us behind our backs?

In earlier, less technically advanced eras, this approach would have been far-fetched. Material goods were inherently difficult to produce, find, and ship. They were rare and precious. They were closely associated with social prestige. Without important material signifiers such as wedding china, family silver, portraits, a coach-house, a trousseau and so forth, you were advertising your lack of substance to your neighbors. If you failed to surround yourself with a thick material barrier, you were inviting social abuse and possible police suspicion. So it made pragmatic sense to cling to heirlooms, renew all major purchases promptly, and visibly keep up with the Joneses.

That era is dying. It’s not only dying, but the assumptions behind that form of material culture are very dangerous. These objects can no longer protect you from want, from humiliation – in fact they are causes of humiliation, as anyone with a McMansion crammed with Chinese-made goods and an unsellable SUV has now learned at great cost.

Furthermore, many of these objects can damage you personally. The hours you waste stumbling over your piled debris, picking, washing, storing, re-storing, those are hours and spaces that you will never get back in a mortal lifetime. Basically, you have to curate these goods: heat them, cool them, protect them from humidity and vermin. Every moment you devote to them is lost to your children, your friends, your society, yourself.

It’s not bad to own fine things that you like. What you need are things that you GENUINELY like. Things that you cherish, that enhance your existence in the world. The rest is dross.

In the sphere of social networks, we talk about the Dunbar number. While electronic computerized networks theoretically allow people to connect with tens of thousands of other people, stable social relationships, according to Robin Dunbar, are limited to a much smaller number.

Dunbar’s number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships. These are relationships in which an individual knows who each person is, and how each person relates to every other person.[1] Proponents assert that numbers larger than this generally require more restrictive rules, laws, and enforced norms to maintain a stable, cohesive group. It has been proposed to lie between 100 and 230, with a commonly used value of 150.[2][3] Dunbar’s number states the number of people one knows and keeps social contact with, and it does not include the number of people known personally with a ceased social relationship, nor people just generally known with a lack of persistent social relationship, a number which might be much higher and likely depends on long-term memory size.

The globalization of the manufacture of household objects has put us in a situation similar to that of online social networks. Theoretically we can own as many things as we can afford. And if we can’t afford them, we can wait until they make their way to the deep discount stores and outlets and then buy them for below the cost of production. These things, by making themselves strange strangers — they raise their hands and step out from the background a stranger in our midst. But once our food and clothing becomes inscribed into our social space and wants to have a conversation about origins and process, can we really keep consuming at our current pace? Will the slots available in the cognitive limit of our Dunbar number now have to include all the objects that are waking up around us in this Internet of things?

We are waking up inside a world that is waking up to find us waking up inside of it.

Comments closed