The fluidity of William Kentridge is astonishing. My mouth hangs open in awe. It’s difficult to even find the words to describe what he does. I’ve just returned from the members preview of his major exhibition at SFMOMA called William Kentridge | Five Themes.

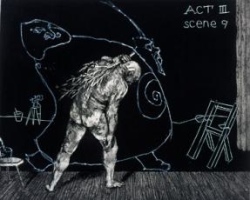

As Kenneth Baker of the SF Chronicle says, “Even people only causually involved with contemporary art tend to bookmark memories by their first encounter with the work of William Kentridge.” Mine was about 4 or 5 years ago at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. I happened upon a small exhibition of charcoal drawings and one of Kentridge’s “drawings for projection.” These hand-drawn films are composed through a process of making a set of charcoal drawings corresponding to the main scenes of the film. A drawing is created, one frame is shot, then a portion of the drawing is erased and redrawn. Another frame is shot. And so on. The palette of the narrative becomes a palimpsest.

The film was called “History of the Main Complaint” and was made after the establishment in South Africa of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The narrative plays out through a ‘medical’ investigation into the body of Soho Eckstein, the white property-developing business magnate– and it eventually works its way around to point the way toward the emergence of conscience and the possibility of reconciliation. This is not agit-prop theater, its politics are filled with poetry, ambiguity and some sharp edges.

Kentridge’s process of drawing a film is a fundamental artistic act, a gesture in four dimensions. Thousands of individual drawings are created and destroyed in the process of making the projectible drawing. Marks are made, erased, new marks are made and erased– and the camera catches each state of the drawing. These fleeting moments of being exist only on film, the individual states of the drawing flash into being and are at the same time, both irretrievably lost and leave ineffaceable traces.

The SFMOMA show includes a performance of Kentridge’s design for Mozart’s The Magic Flute through projections on a very large toy theater. The YouTube videos have embedding disabled, so you’ll need to click the links to view them.

While working on Magic Flute, Kentridge concieved another piece called “Black Box.” It’s a stunning piece of work. Stop whatever you’re doing, go to SFMOMA and watch this work from beginning to end. It’s another mechanical theater piece consisting of animated film, kinetic objects, drawings and a mechanical actors/puppets. It is a powerful piece of political theater, a Trauerarbeit machine. (These videos don’t do it justice)

Kentridge discusses the role that memory and mourning play in his work:

There was a term someone introduced to me that I’ve kept in my head for Black Box, it’s the word Trauerarbeit – the work of mourning. Freud writes about that in 1917 in Mourning and Melancholy.

Freud talks about how memory compares to reality and what it takes to arrive at an objective view once the lost object is actually gone. It’s a process of detachment and de-vesting.

A Trauerarbeit machine on stage could turn, and things would come out of it.

Kentridge works without a detailed plan, here he discsuses the moments before the real-time flow of his work begins:

“Walking, thinking, stalking the image. Many of the hours spent in the studio are hours of walking, pacing back and forth across the space gathering the energy, the clarity to make the first mark. It is not so much a period of planning as a time of allowing the ideas surrounding the project to percolate. A space for many different possible trajectories of an image, where sequences can suggest themselves, to be tested as internal projections. …It is as if before the work can begin (the visible finished work of the drawing, film, or sculpture), a different, invisible work must be done. A kind of minimalist theater work involving an empty space, a protagonist (the artist walking, or pacing, or stuck immobile) and an antagonist (the paper on the wall).”

A contradiction must be captured, Kentridge must make a clear mark that preserves the ambiguity of his original impulse. It’s writing under erasure. Time, memory, history, humanity and reconciliation inhabit his work.

It happened at some point. While I’ve been following Kentridge for a number of years, I missed the moment when he emerged as the artist for this generation. If you’re not conversant with his work. Seek him out, his work touches all the notes in the central narratives of our time. And indeed, time itself.

2 Comments