Resolved: it’s an article of faith that higher resolutions are better. I want to take you higher. The way to get a higher resolution is to start with the density of pixels or the sampling rate. Sound and vision. The more information packed into each unit of measure, the higher the resolution of the image. Clarity and “realistic-ness” are the qualities we attribute to high resolution images. The image was so clear, it was just like the real thing. I couldn’t tell the difference. Was that live or a recording?

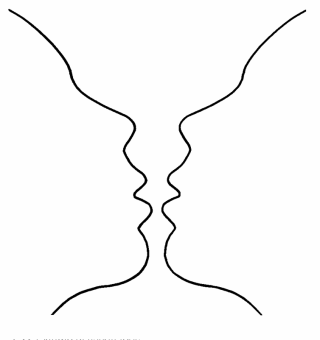

McLuhan talked about hot and cool media. Hot media is high definition in the sense that the viewer can’t get a word in edgewise. The media, and its content, is projected toward the senses filling up all the space, there is little or no room for the viewer to fill in the gaps. The interpretive faculties are overwhelmed and retreat. Cool media leaves spaces for the viewer to project herself into the stream. When the viewer fills in the gaps a different kind of richness, or density, is created. Each strategy absorbs the viewer in a different way.

“Big Data” is another form of high definition. More data points, bigger sample sizes bring more statistical clarity. Meta-figures emerge from Big Data that aren’t available from the perspective of the civilian on the ground. These meta-figures provide probabilities of future outcomes and are reliable to such an extent that corporate strategies are based on them. In the light of high def big data your future possibility space has become both visible and has had probabilities assigned to each vector.

There are two uncanny moments when it comes to the experience of high def. The first is the well-known idea of the uncanny valley. That’s the creepy feeling we get when a simulation of a person is just a little off, just short of perfection. We are both attracted and repelled, the experience is close enough to the real that we’d could be easily sucked in. But we’re creeped out by the idea of being sucked into a simulation — in the sense that it isn’t alive and real, but an illusion of life created out of dead matter.

The second uncanny moment is more subtle. When Steve Jobs was standing on stage selling the benefits of high-definition retina screens, he made the argument that these new screens matched the capability of the human eye to perceive visual data. For humans, the retina screen is the finest viewing experience available. This also happens with audio recordings. When designing codecs and compression strategies, the science of the human ear and the process of hearing is taken into account. The idea behind MP3 compression is to remove the sound that is unhearable by humans resulting in a smaller file size. What you don’t hear, you won’t miss.

This means that as we move toward higher and higher resolutions we reach the end of the capabilities of our perceptual apparatus. Our senses begin to fail us. We keep adding visual information to the picture, but the picture doesn’t change. All the instruments agree that the resolution is getting better. The unaided eye and ear face the uncanny moment when invisible change begins to occur. The picture gets better and better, but for whom is it getting better?

It’s in the world of recorded audio that we see the most passion when it comes to the ability to hear beyond the capacity of humans to hear. Audiophiles purchase stereo equipment and special recordings that reproduce both hearable and unhearable sound. It’s an invisible material difference that’s measurable, yet imperceptible. This non-human form of high-fidelity recording technology no longer uses humans as a reference point. Audiophiles claim that humans can hear the difference and to settle for less is a moral failing in the commercial market for audio recordings.

On the road to higher definition visuals, the state of the art appears to be High Frame Rate 3-D. Peter Jackson released a version of his film of “The Hobbit” in the highest-definition visual recording technology yet created. The purpose of this technology is to get even closer to reality — to show how it really is with seeing. At 48 frames per second, HFR is well within the upper bound of 55 fps for human seeing. So at this point, there is no unseeable information in the image.

In comparisons between the HFR 3D and standard 2D versions of the film we get an object lesson in McLuhan’s hot and cool media. Many viewers coming to the film for the first time had trouble following the details of the story in HFR 3D. Peter Jackson, who knows the story on a frame-by-frame basis, prefers to watch the HFR 3D version. Jackson believes the HFR 3D version provides a more “immersive” experience. For an average audience member, the HFR 3D version leaves no gaps. For the director there are plenty of gaps between what’s on the screen and how he imagined the film.

As our technologies are able to provide higher and higher resolution reproductions to our senses our own finitude is exposed. Historically resolution has been limited by cost. Higher resolution cost more and therefore wasn’t widely used. As cost becomes less of an issue, aesthetic judgement moves to the foreground. If you make your home movies in HFR 3D will that preserve a record of how it really was? Is it live or is it Memorex?