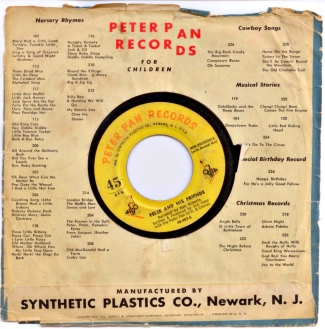

We seem to have lost the liner notes. On some labels and for some artists the liner note provided a context or key to the music contained within. Reading song lyrics while listening to an album for the first time was an important ritual. Before the counter-culture was totally absorbed into mass culture, the photographs on the album were a window into a new form of life. An album required decoding and the casing provided some of the clues.

For those too young to remember, the liner note was an essay, photographs, lyrics, credits, etc., usually printed on the inner sleeve of a vinyl record album. The sleeve that held the vinyl platter was called a record liner, sometimes referred to as a dust jacket. When commercially recorded music became digital bits there was no need for a dust jacket and thus no where to print the liner notes. The material relationship of the liner note to the physical media that holds the encoded music can’t be replaced with hyperlinks.

The record album created the perfect canvas for the liner note. Its size was more like an art book, plenty of room for the interplay of text and image. The compact disc shrunk everything down to an unreadable size. Text is still printed on compact disc packages, but only as a matter of form. It’s like those credits that roll by at hyper speed at the end of a television show. You know they say something, but they’re not really meant to be read.

Allen Ginsberg writing about Bob Dylan’s album “Desire” is my strongest memory from the heyday of liner notes. Listening to the music through Ginsberg’s lens connected it to a long line of poetry and song. Long afternoons lying next to the stereo, reading and discussing the notes, listening to the tunes, parsing the lyrics until they were burned into memory.

Recently I’ve had a similar experience with poetry and podcasts. While footnotes to the poetry of Wordsworth and Milton don’t always give me the same charge — listening to close readings of the poetry is like getting a great set of liner notes. Here are a few that I’ve listened to more than once:

• On Wordsworth

On Wordsworth

Professor Timothy Morton

Rita Shea Guffey Chair of English Literature

Rice University

• On Milton and Wordsworth

On Milton and Wordsworth

Professor William Flesch

Brandeis University

If liner notes were to make some kind of comeback, I think they might look more like what Anil Prasad does with his web site Innerviews. His interviews with musicians are completely different than anything you’ll find in the commercial music press. His writing opens up both the players and the music. When I first discovered it I realized that I’d missed years of great interviews. I spent days going from Bill Bruford to Allan Holdsworth to Zoe Keating to Laurie Anderson, and then to Marc Ribot and Joan Jeanrenaud. I have to be very careful about visiting Innerviews. I start reading and when I look up, several hours have passed and I wonder if I can squeeze in just one more interview.

Another possibility for liner notes is the video note. Here, soprano Joyce DiDonato talks about singing an aria from Rossini’s “La Donna del Lago.” This is a warm up for a concert, but it would be a welcome addition to a recording.

The video liner note that kicked off this whole train of thought was the DVD that accompanies Jeremy Denk’s new recording of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.” Denk is both a writer and a musician, and is particularly adept at taking you inside the music and the experience of playing it. Listening to Denk talk about what he’s playing is much like listening to Timothy Morton read and interpret Shelley’s poem “Mont Blanc.” You go back to the work with new eyes and the aesthetic object unfolding in front of you bristles with new possibilities.

The liner note was physically linked to the media it described. You’d think in an age where the hyperlink has become so dominant that liner notes would proliferate. But like a restaurant with hundreds of online reviews, you have trouble knowing where to turn. You need a review of the reviewers to even get started. Here the economy of abundance is a detriment, it’s the limitations that force the liner note to be something special.

A last liner note, this one also by Jeremy Denk. I’d always had trouble hearing Gyorgy Ligeti’s piano etudes. Somehow my ears weren’t quite ready. A work of art asks you to attune to it in a certain way. To see perspective in a classical painting, you need to stand in a certain spot with respect to the canvas. Listening to music is much the same. Sometimes it’s the liner note that tells you where to stand.