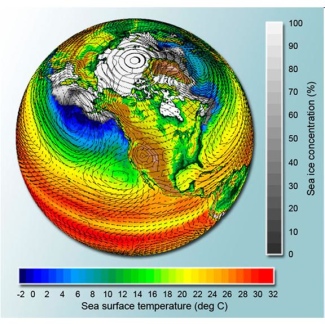

Climate is a interesting kind of thing. It’s not directly perceivable through our senses. Weather isn’t climate, rather it’s a data point used in the construction of the larger conceptual model we create to visualize climate. There’s our model of climate, and then there’s the thing-in-itself that is climate. Particular manifestations of weather are a result of climate, but the unseasonable cold, rain and snow aren’t climate.

Watch out you might get what you’re after

Cool babies strange but not a stranger

I’m an ordinary guy

Burning down the houseHold tight wait till the party’s over

Hold tight We’re in for nasty weather

There has got to be a way

Burning down the house

Weather is what you experience, climate is the set of conditions that provide the ground for the possible weathers that might manifest at any particular moment. Equatorial climate has a range of possible weathers, as does Antarctica. Strange weather, if it occurs with enough frequency becomes climate—that is to say that it joins the set of possible weathers as a probable weather manifestation.

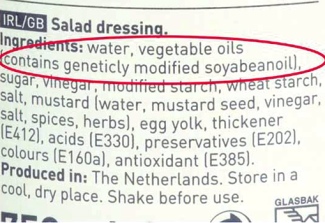

When we say that we must address the climate, it’s not the climate we would directly touch. For instance, reducing or eliminating carbon dioxide emissions as a negative externality from our machines is an attempt to address a specific chemical reaction in the atmosphere known as the greenhouse effect. By changing the pattern of global warming, we hope to affect the climate—meaning the range of possible temperature and weather manifestations.

“You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.”

The climate has an interesting political feature that is of recent vintage. Our interaction with the Internet is perhaps the best model. The Network can be addressed from any node. There is no center or edge. Monarchs, dictators, elected governments, corporations, non-profit groups, political parties, religions, scientists, artists, hobbyists and individuals can all connect their ideas to the Network. No special authority, coordination or consensus is required to publish. Tap a few keys on a keyboard, make some kind of recording, and then push a button.

As we become more pessimistic about collective action on global warming, the issue of geoengineering becomes more and more pressing. Geoengineering treats the earth, its atmosphere and biosphere, as a machine that can be hacked through large-scale interventions to operate within parameters that we specify. Generally these techniques aim to manage solar radiation or to directly remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The key question about geoengineering is who is allowed to geoengineer? In some sense, we’re all collectively geoengineering the earth through our use of a certain class of carbon-emitting machines. But the large interventions proposed by geoengineers need not be collective actions sanctioned by governments. Geoengineering requires only the resources and access to the climate.

Bill Gates has enlisted climate scientist Ken Caldeira to co-manage a fund that invests in geoengineering research. Caldeira is not currently advocating the use of geoengineering, but he puts it this way in an article by James Temple in the San Francisco Chronicle:

“I am in favor of fire insurance,” he once said in explaining his stance. “But I am also against playing with matches while sitting on a keg of gunpowder.”

In other words, if we pass the rubicon we’ll have geoengineering in reserve as a last resort. The “fire insurance” metaphor is a little troubling. Who plays the role of the insurance company in this scenario? Who will decide when the house has burned down? What store shall we go to purchase replacements for the contents of our house? Businessman Russ George recently accepted a payment of $2.5 million to dump 100 tons of iron dust into the Pacific waterways off of western Canada. The scientific community was outraged by his actions, but should we really be surprised by this kind of hacking? The triggers for geoengineering are not as clear as a house on fire.

The residents of a small island threatened by rising oceans may well decide that the time is right to engage in geoengineering. A tech billionaire may decide it’s up to him to act in the absence of collective action to address global warming. Two enemy states may decide to engage in geoengineering as a form of warfare. A politician may decide it’s good politics. The appeal of geoengineering is that it doesn’t necessarily require collective action. No agreements need be reached. We only need to find the weather to be sufficiently strange.

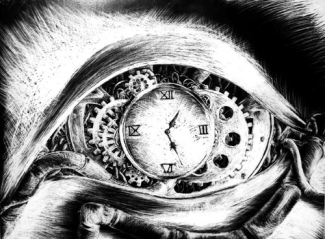

The other appealing thing about geoengineering is it makes the invisible visible. The problem with climate change as a result of global warming is that it’s inaccessible to us. It’s what Timothy Morton calls a hyperobject. It occupies a higher dimensional phase space—it unfolds too slowly over too long a period for our eyes to perceive it. We are outscaled by it. Geoengineering allows us to take immediate concrete action. The vast geologic time scales are compacted to fit into human lifetimes. If the problem is not solved, at least it’s been cut down to size. Some may call geoengineering “playing god” with the earth, but it’s more a matter of bringing the “earth” down to earth, a human-sized earth (humiliation).

If geoengineering fails, don’t worry. We can always go back in time and repair the mistake. Just as with repairing the machinery of the biosphere and the climate, time travel and correcting the course of time is only a matter of technology advancing sufficiently. The filmmaker Chris Marker imagined what the correction of catastrophe might look like in his film La Jetée: