We do a lot of our thinking through glass and mirrors. We want our words to properly reflect the world. We insist that as we observe the world, our glasses should be free from any rose-colored tint. And when a glass knowingly distorts the world, we ask that it be properly labeled.

Philosopher, Tim Morton, uses the passenger-side wing mirror of the America car to talk about the rift between an object and its aesthetic appearance. This is how he describes it in the introduction to his book, “Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, Causality.”

Objects In Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear

An ontological insight is engraved onto the passenger side wing mirrors of every American car: Objects in Mirror are Closer than They Appear. What we take to be the object “behind” its appearance is really a kind of perspective trick caused by habitual normalization of the object in question. It is my habitual casual relation with it that makes it seem to sink into the background. This background is nothing other than an aesthetic effect—it’s produced by the interaction of 1+n objects. The aesthetic dimension implies the existence of at least one withdrawn object.

Another way of talking about this “habitual normalization of the object” is to reverse the surface/depth binary. Traditionally, the real is deep underneath and the surface is the accident of a temporary condition. Objects behave normally when they occupy a clear place in one’s performance of habit. Weird distortions of appearance are surface phenomena that will clear out given enough time. Morton reverses these observations. Objects undergo a distorting normalization in our everyday lives. It’s when objects become unfamiliar and weird that their deeper reality clearly begins to show itself not as deeper, but as closer than their appearance.

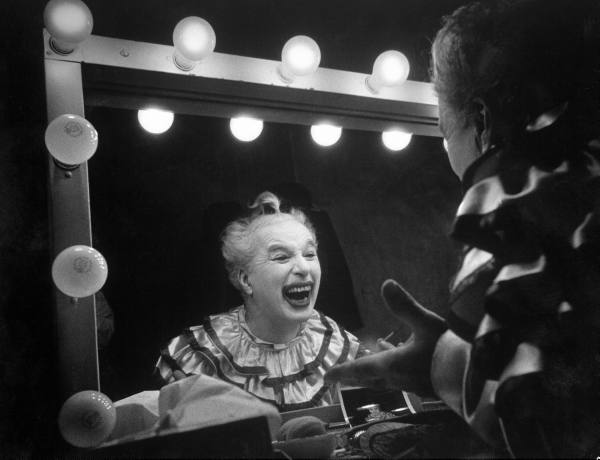

While traveling for his many speaking engagements, Morton finds himself in unfamiliar cities, displaced time zones and strange hotel rooms. The real intrudes, not as a comforting solidity, but rather as a “hallucinatory clown.”

Objects in mirror are closer than they appear. This is the real trouble. The real trouble is that my familiar light switches and plug sockets—or rather my familiar relations to these objects—is only an ontic prejudice, an illusion. The REALITY is what I see as the illusion-like, hallucinatory clowns that lurch towards me, gesturing and beckoning (but what are they saying?).

The incident that brought me back to glass and mirrors was listening to a song by Australian singer-songwriter Courtney Barnett called “Dead Fox.” It has a chorus with the lyrics,

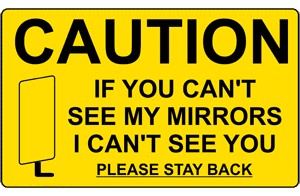

If you can’t see me, I can’t see you.

The lyric refers to the sign you’ll see on commercial trucks warning other drivers in the proximity that if you can’t see the truck driver’s wing mirror, then he can’t see you. And therefore, he will behave as though you don’t exist, after all, you’ve had fair warning.

We imagine the possibility of a cyborg future and think of some strange grafting of machine to flesh. But perhaps it’s much simpler than that. Our first instantiation as a cyborg was with the broad distribution and ownership of the automobile. We’re never more human than when our access to the world is limited to the view through glass and mirrors. The car gives us all that and the ability to move much faster than an ordinary human.

Courtney Barnett’s “Dead Fox” presents a cartoon of the reality of our cyborg existence. We head down the highway splattering roadkill across the blacktop. Pollen floats into the car causing a sneeze resulting in a dangerous swerve. A truck driver checks his mirrors and then passes on the wrong side without signaling. Because if “you can’t see me, I can’t see you.” Esse est percipi.

Heading down the Highway Hume

Somewhere at the end of June

Taxidermied kangaroos are lifted on the shoulders

A possum Jackson Pollock is painted in the tar

Sometimes I think a single sneeze could be the end of us

My hay-fever is turning up, just swerved into a passing truck

Big business overtaking

Without indicating

He passes on the right, been driving through the night

To bring us the best price

Morton’s passenger wing mirror tells us something about objects outside of our habitual day-to-day life. We normalize objects into a background upon which a weird reality floats. Barnett’s mirror gives us a sense of the absurd tunnel vision we’ve forced upon ourselves—we barely even see the roadkill we’ve “jackson pollocked” across the tar. Big business tells us that unless we can see their mirror, we’re standing in the wrong place. And if we’re standing in the wrong place, we’d better give them a wide berth.

The temptation is to go around breaking glass as though it were to blame for the use we make of it. But Morton and Barnett show us that we only need to let the weirdness of glass come to the surface. Somehow we’ll need to forge a new alliance with glass – perhaps moving beyond perfect transparency and reflection to imperfection and distortion. If we turn this thought and look at it from a slightly different angle, we can talk about developing an appreciation for the beauty of translation.