It’s a book of poetry, although in it’s most complete form, it’s not exactly a book. It’s more of a CD-ROM, if there were such a thing anymore. You could describe it as a multimedia presentation with words, animated images, music, comic strip panels and recitations. Igor Goldkind’s new publication “Is She Available?“, despite its intentional defiance of category, probably should be called poetry.

Full disclosure: I’ve counted Mr. Goldkind as a friend for almost four decades. This reading is of the text, a little of my friend, and the journey of a poet.

Perhaps the best example of poetry making in this mode would be the work of William Blake — the poet, painter and printmaker. Blake was also a technologist. He invented relief etching to combine words and imagery on to the same printing plate. When we read his poetry today, for the most part, we read it extracted from its original context — simplified as though we were looking at a web page in “reader view.” The poem’s text is transformed into its most legible and conservative form. The images are removed and the typography tamed. Although we find it fascinating, critics have trouble producing a close reading of a work that broadcasts on so many different channels. Film, or video game, criticism may come closest to accounting for all the levels.

I put these poems into the larger frame of a poet’s journey. Joseph Campbell called it the Monomyth, or the “Hero’s Journey.” The poet leaves home, wanders and experiences the world, and then returns home, both changed and unchanged. For this poet, home was San Diego, California, when it seemed like the city lacked everything. It was a time before the Internet and corporate franchising made every place much the same. Looking outward, the rest of the world appeared filled to the brim — the location of danger, culture, and life. I’m going to examine four parts of the text that bring this theme into relief.

Whatever the format, the reader will be faced, first of all, with the title. The work is called “Is She Available?” Who is this “she?” Is “she” that obscure object of desire? Is she a lover, a daughter, mother, or perhaps she’s the muse of poetry itself. Whoever she is, she’s absent. There’s a separation, an aesthetic distance from which she’s viewed. The phrase also gives us a sense of her allure, her magnetism. At the outset of the poet’s journey, “she” may well be the call of the road — the as yet unfulfilled promise of the wider world.

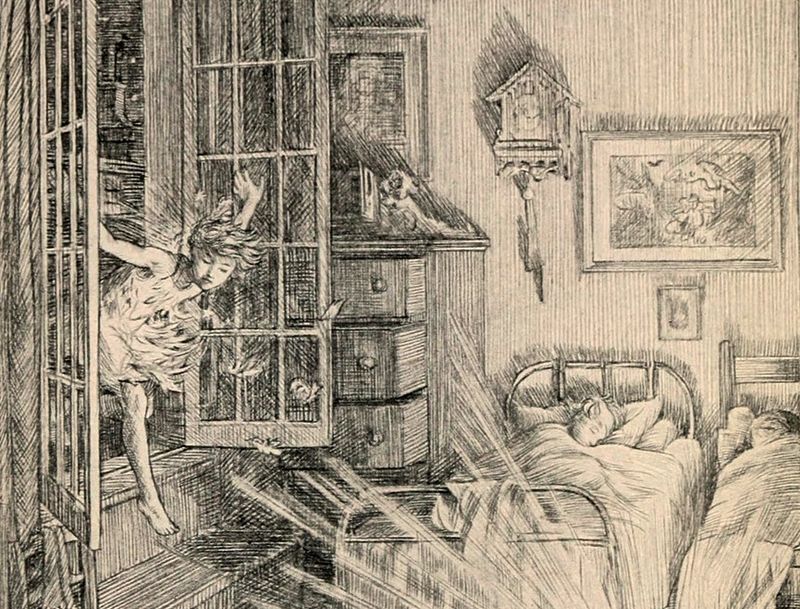

In the poem “What Peter Said to Wendy” we see the mechanics of desire, and of the journey. If desire were to be fulfilled, then the journey would be over before it had even begun. For the journey to continue, the object of desire must be desire itself — the desire of desiring. In the story of Peter Pan and Wendy Darling, Peter resides in Never Never Land. It’s a place where time idles in childhood reverie. Wendy knows at some point she must return to the world. Peter knows that he needs to give Wendy something she can take back, even if he can’t follow her there.

From “What Peter Said to Wendy”

Fear not my audacity Wendy.

I do not care for your heart, as you might think, I care for mine

And the reflection of truth’s desire I see hiding

in the forest of your eyes

It’s in the journey that the contours of the poet’s life come in to focus. Each of the poems in the volume encapsulate a moment along the path. Textures that were invisible in the youth of small town Southern California are now clearly visible. Family connections received and created take hold with real and vital force. There are battles with daemons both internal and external, and the poet tries on a series of masks to see how they fit. Think of it like a medicine man tasting all of the plants in the surrounding landscape to get of sense of their effect on the human mind and body. There’s nothing more real than this.

At the far edge of the journey, the poet encounters a mirror image of his starting point. For a long time San Diego felt like a very large village. Perhaps, it’s a city now, but it remained a small town for the longest time despite its ballooning population. At first walls were built to keep the poet in, and he had to escape. Now, in this village out in the world, they’re built to keep him out. In the poem “Dry Stone Walls”, he encounters the narrow attitudes that first inspired his journey into the wider world.

You can’t build a wall round a village

You can try

You can stack honeyed stone upon stone, fashion judgement upon judgement,

into a long pretty barrier of decorative limestone

to keep the outsiders out and the insiders in

But you can’t build a wall round a village

the sun and the wind

will always find their way in

In the prototypical “Hero’s Journey”, the hero engages in a climactic battle and emerges victorious. This moment signals the change that allows him to return home. In this work, it’s the poem “Dry Stone Walls (You Can’t Build a Wall Round a Village)” that serves this purpose. The battle that he didn’t wage at home is fully engaged here. And it’s not that Frankenstein’s Creature somehow turns round and defeats the villagers, with their torches and pitchforks, but rather like “the sun and the wind”, the poet can now come and go as he chooses. The walls don’t and can’t keep the wider world at bay. The narrow attitudes of the village have lost their force, and the atmosphere of the wider world has equalized with his point of origin. San Diego has become a part of the wider world; the spell has been broken.

The poem “San Diego Bay” marks the poet’s return. Filled with the experiences of the world, he is gigantic compared to the young man of so many years ago. San Diego Bay is now the size of a bath tub, and the giant poet washes off the dust of the road in its waters.

San Diego bay… Oh San Diego bay

Your leaden toy war ships cast a heavy grey cloud

on my sunlit-blue sky return.San Diego bay… San Diego bay

You rounded sheet of crinkled foil at six AM in the morning looking out, looking in, at the sheet of this world, I bathe in you now.San Diego bay

San Diego bay

You’re my Dirty

bathwater

now.

Igor Goldkind’s “Is She Available?” is filled to the brim with sparkling and challenging poetic sketches forged during his travels. The e-book is a thrill ride that’s built up layer-upon-layer on a bedrock of poetic text. This collection of poems isn’t the well-behaved straight lines of text you may be used to; they explode into sound, music and image; refusing the standard-issue poetry container.

The form of this “book” is another dimension of the journey these poems take us on. The physical form of the poems, their inscription on a multimedia surface, stops the reader’s internal voice from assuming an open-mic night, timid, confessional, “poetry voice,” and demands something more. It’s a loud book and may not be appropriate for reading in a quiet library. In fact, one of its more challenging technical aspects is figuring out the dynamic range of the poem’s sound. There may be a temptation to let the “book” read itself to you. But to take in its full effect, you’ll need to perform it yourself, at full volume.