There was a shift in momentum, the reading we do on web pages and the reading we do with printed books joined together in the Kindle and the iPhone. The movement was from perceiving the situation as ‘either/or’ to one of ‘both/and.’ The question about one thing replacing another suddenly seemed less important. Another point of access was opened, another door.

Consider the following sequence:

- This library contains one-of-a-kind handwritten manuscripts

- This library contains manuscripts and copies of manuscripts, both produced by hand

- This library contains manuscripts, copies of manuscripts and printed books

- This library contains printed books and audio/visual media encoded in celluloid, vinyl, recording tape and CD/DVD

- This library contains printed books, encoded audio/visual/textual materials and a connection to the Network to view web pages

- This library contains printed books, encoded audio/visual/textual materials and a connection to the Network to view web pages and digitized audio/visual/textual materials.

- This library contains printed books, encoded audio/visual/textual materials, a connection to the Network and loans out eReading devices that can contain and connect to any digitized media.

- This library contains nothing. It makes digital media available to its members via the Network through a variety of reading, viewing and listening devices

A library moves from a building that contains things to a service that enables connection to things.

Note: this change in the distribution network also reveals the converging business models of for-profit and non-profit journalism. But that’s a discussion for another time.

Now consider this eReading use case:

I’m reading a hardcover printed novel in my favorite chair. I get to a stopping point and mark my place with a bookmark, and I use my iPhone’s camera to send a bookmark to the Network. Later, I pick up my eReader, find my place and continue reading. I’ve got to go meet a friend so I mark my place and then drive over to a cafe. In the car, I turn on the streaming audio version of my book. It’s remembered my place, and picks right up with the story. I arrive at the cafe, mark my place and then go in and sit down. My friend is late, so I pull out my iPhone, find my place and continue reading. My friend arrives, I mark my place and start talking to my friend about this facinating novel.

We have the sense that the book is the container that holds the words. The library sequence above tells us something about the changing technology of the containers and the contained. As the book itself breaks free of a specific container and allows us to interact across multiple access points, all we ask is that the particular sequence of words be preserved and that our current place be available when we need it.

If the book isn’t its container, but rather a fixed stream of words that can be accessed through a variety of devices, are we fundamentally changing our idea of the book? When we buy a “book” are we buying access to the stream of words via a particular set of methods?

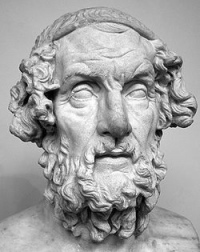

This way of talking about books as a stream of words brings to mind an older form, the tradition of oral storytelling. Homer, if there was such a person as Homer, sang the stories of the Iliad and the Odyssey to an audience of listeners. A significant difference: in the oral tradition, variation in the word sequence is part of the value proposition. In modern books it would simply be considered an error.

As textual media moves toward a digital stream the boundries between and among books become more ambiguous. We’ve become used to the idea that search functions are available for individual digital books. As the community of digital books grows, we will also have search among books. Search will be unbounded to play in the intertextuality of all books. We may be traveling across the connections between books just as today we traverse the hyperlinks of the web. But the linkages aren’t just matching bits of text here and there. They aren’t just words, they mean something.

The idea of all books becoming one book– and of books becoming intimate, brings to mind the work of Norman O. Brown. Specifically the preface to Closing Time:

Time, gentleman, please?

The question is addressed to Giamattista Vico and James Joyce.

Vico, New Science; with Joyce, Finnegans Wake.

“Two books get on top of each other and become sexual.”

John Cage told me that this is geometrically impossible.

But let us try it.

The book of Doublends Jined.

At least we can try to stuff Finnegans Wake into Vico’s New Science.

One world burrowing on another.

To make a farce.

What a mnice old mness it all mnakes!

Confusion, source of renewal, says Ezra Pound.

Or as James Joyce puts it in Finnegans Wake:

First mull a mugfull of mud, son.

As rational metaphysics teaches that man becomes all things by understanding them (HOMO INTELLIGENDO FIT OMNIA), this imaginative metaphysics shows that man becomes all things by not understanding them (HOMO NON INTELLIGENDO FIT OMNIA).

As Brown reminds us, books have never been separated, their containers are a kind of illusion, encoding only an instance of a song. The dark territory between texts is murky, and we may need to mull a mugfull of mud before we find anything of value. And value can be found both in ambiguity and in clarity.

Joyce was known for writing down a stream of consciousness and printing it out as something that resembled a novel. It’s a river that runs through all of us. And in Joyce, the streams of books, and the streams of consciousness are joined as when the child was a child…

When the child was a child

It walked with its arms swinging,

wanted the brook to be a river,

the river to be a torrent,

and this puddle to be the sea.When the child was a child,

it didn’t know that it was a child,

everything was soulful,

and all souls were one.

reading a book that entrances you on a white page and on the breast tit of the computer screen i think induces a different kind of reception, unconsciously of it. i haven't read anything on “kindle” or the like, and I may be wrong that that experience resembles reading on a computer screen. i think it matters what you read, too. whether, say, it is a news story – even there i prefer the new york times print edition, but haven't the time for all of it each day, thus skim, but read friday and tuesday's thoroughly. the explosion of information available is quite wonderful: but the brain needs time to digest, and it has quite a few different stomachs!

Sunday Morning Reading…

Some Sunday morning reading to share. Frank Rich looks at Our Town. Or rather our world through Wilder’s classic. Classic itself. Best Rich I’ve read in awhile. Thomas Friedman quotes from The Onion and Paul Gilding who calls what we’re……